Hospital Billing Explained

The following is an explanation of hospital charges, payment and costs.

The mission of each and every hospital in America is to serve the health care needs of the people in its community 24 hours a day, seven days a week. But, hospitals’ work is made more difficult by our fragmented health care system — a system that leaves millions of people unable to afford the health care services they need.

Hospitals deal with more than 1,600 insurers. Each has different plans and multiple and often unique requirements for hospital bills. Add to that decades of government regulations, which have made a complex billing system even more complex and frustrating for everyone involved. In fact, Medicare rules and regulations alone top more than 130,000 pages, much of which is devoted to submitting bills for payment.

Today’s fragmented health care system leaves hospitals with a daily balancing act to maintain their mission to the community while making ends meet. While the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) should improve coverage, many of these chronic problems will persist.

The following is an explanation of hospital charges, payment and costs.

Charges vs. Payments

Federal laws and regulations require hospitals to maintain uniform charge structures. Payments, however, do not correspond to those charges. What a hospital actually receives in payment for care is very different. That is because:

- For Medicare patients, about 41 percent of the typical hospital’s volume of patients, the U.S. Congress sets hospital payment rates.

- For Medicaid patients, about 24 percent of the typical hospital’s volume of patients, state governments set hospital payment rates.

- Private insurance companies negotiate payment rates with hospitals. Privately insured patients make up 31 percent of the typical hospital’s volume of patients. Private insurance company payment rates vary widely. Larger insurance companies typically are better positioned to demand bigger discounts.

- Tax-exempt hospitals are prohibited from billing gross charges for those eligible for financial assistance. Under the ACA, tax-exempt hospitals are required to have a written financial assistance policy that is widely distributed in the community. Care is either provided for free, or based wholly or partly on Medicare rates under the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) regulations.

- Those insured patients who are seeking care at a hospital outside their insurance company’s network, as well as patients whose care is paid for by other types of insurance (e.g., worker’s compensation, auto liability insurance, etc.), are billed full charges.

Source: HCUP Fast Facts. AHRQ. November 2017.

Payments vs. Costs

How do these government-set and insurance company-negotiated payments compare to the actual cost of providing hospital care to patients? Medicare and Medicaid pay less than cost, the uninsured pay little or nothing, and others must make up the difference.

- Medicare and Medicaid pay less than the cost of caring for program beneficiaries – an annual shortfall of $68.8 billion borne by hospitals.

- Hospital uncompensated care, both free care and care for which no payment is made by patients, makes up about 4 percent of the average hospital’s costs.

- Privately insured patients and others often make up the difference.

Payments relative to costs vary greatly among hospitals depending on the mix of payers.

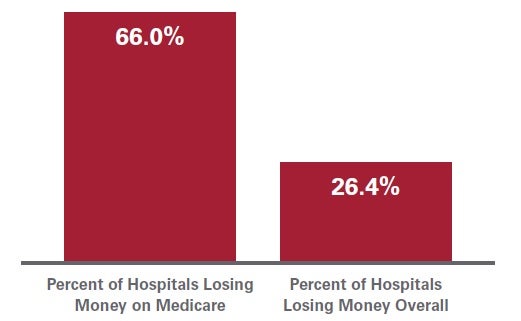

Percent of Hospitals Losing Money, 2016

In 2016, two-thirds of hospitals lost money providing care to Medicare and Medicaid patients and nearly one-fourth lost money overall (see chart below).

Source: American Hospital Association Annual Survey data, 2016 for community hospitals.

In addition to the high number of uninsured people in America, the hospital payment system itself is broken. Government programs like Medicare and Medicaid pay hospitals less than the cost of caring for the beneficiaries these programs cover; insurance companies negotiate deep discounts with hospitals; and many people who are uninsured pay little or nothing at all.

These inequities in payment leave hospitals with an annual balancing act – hospitals must ensure that the payments they receive for care from all sources exceed the costs of providing that care. A hospital cannot continue to lose money year after year and remain open. Hospitals need a positive bottom line in order to be able to replace or improve old buildings, keep up with new technologies and otherwise invest in maintaining and improving their services to meet the rising demand for care.