A Recipe for Disaster Preparedness: Northeast State Execs Gather to Discuss Emergency Preparedness Strategies

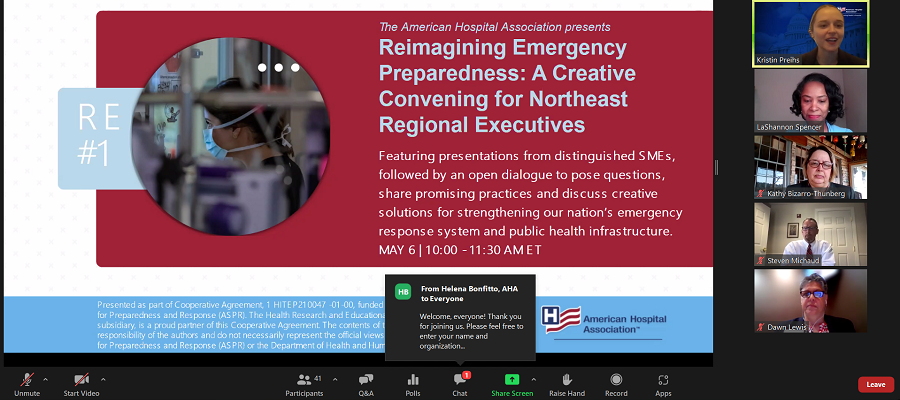

TOP: The panel of speakers begins the AHA Region One Creative Convening on disaster and emergency preparedness. Top-down: Kristin Preihs, AHA Director of Clinical Quality, Grants and Contracts; LaShannon Spencer, AHA Region One Executive; Kathleen A. Bizarro-Thunberg, New Hampshire Hospital Association Executive Vice President of Federal Relations; Steven R. Michaud, Maine Hospital Association; Dawn Lewis, Hospital Association of Rhode Island Healthcare Emergency Management Director | May 6, 2022, via Zoom.

The importance of emergency and disaster preparedness is instilled in people from a young age. Schools, families and communities teach children what to do in the event of a fire or where to seek shelter during a powerful storm. Most teenagers are taught how to change a flat tire or perform CPR. By the time of young adulthood, the general population has been exposed to all sorts of emergency preparedness protocols — for plane crashes, cyberattacks, downed power lines, stroke first aid and more.

Being prepared for these disasters can reduce the fear, anxiety and losses that accompany them, which is why safety planning is a staple for just about every organization’s operating procedures. But what if an organization is inherently involved in treating those affected by disasters and emergencies — and doing so during the immediate aftermath of an event, during the most vulnerable of times?

What is the most important part of emergency preparedness? Who makes decisions for others during a crisis? And how have pandemics, hurricanes and mass casualty events informed recent developments across health care disaster preparedness?

The American Hospital Association (AHA) and its non-profit affiliate the Health Research & Educational Trust (HRET) recently held a virtual convening for 50 health care executives and public health leaders from the Northeast, including Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont.

The event was “an opportunity to creatively and proactively convene with one another” and reflect on key lessons learned from COVID-19, according to opening remarks from LaShannon Spencer, an AHA Region One Executive. It also was an occasion to “build upon what we have learned in strengthening the cross-sector coordination and collaboration throughout our region to be better equipped to prepare for and respond to future emergencies.”

At the top of the program, three state hospital association executives shared their insights on how the field can move forward, beyond COVID-19. The discussions included key considerations for health care organization, public health departments and nontraditional partners and what lessons have been learned from the pandemic.

“All of a sudden, we were having daily Zoom calls with our state officials. We had unprecedented involvement with our chief medical officers,” recalled Maine Hospital Association President Steven R. Michaud, discussing the early days of the pandemic and the role that MHA played in the state’s response. “We also established, right from the beginning, several work groups that involved key people from the hospitals and systems. We had a work group on PPE. We had a work group on modeling. We had a policy work group. We suddenly were talking to everybody.”

Dawn Lewis, Healthcare Emergency Management director at the Hospital Association of Rhode Island, echoed similar sentiments regarding the sudden, increased communications demands across sectors.

“We identified that communications representatives tend to be brought in a bit too late, often toward the end of an event or process,” said Lewis. As an event would start to unfold and change, “we would realize that we have to report that to the public, so communications needed to be brought up front and early to educate the public and explain, in layman's terms, the necessary mitigation techniques.”

The emphasis on cross-sector teamwork and collaborative communications strategies were frequent talking points for all the executives. To that extent, much of the event’s conversations centered on how to initiate processes to address these inadequacies.

According to New Hampshire Hospital Association Executive Vice President Kathleen A. Bizarro-Thunberg, she and her colleagues saw their role as a state hospital association to be a bridge — a liaison between the hospitals and public health departments.

“There was so much information flowing, especially in the early days [of the pandemic], that we tried to be the central source of that information,” Bizarro-Thunberg explained. “To that end, we created a daily email for our membership that included reports on COVID-19 metrics, time-sensitive clinical updates, public health guidance and requirements for our state partners as well as what we saw coming from the federal government.” She said she empathized with public health departments that were overwhelmed and unable to share this information with hospitals on a regular basis.

Bizarro-Thunberg added: “There was just no way that public health could handle the volume of questions coming from the hospitals, so we served the role of gathering those questions from hospitals and packaging them for public health” before disseminating the information back to the hospitals.

In addition to operational and communications needs, myriad other priorities and recommendations were made by the panel. This included a need to reexamine the topics of modeling, data aggregation, scaling, surveillance and outdated lab/diagnostic technology since all had a direct impact on key issues like hospital bed management, patient movement, workforce scheduling, surge capacity and decision-making toward the overall delivery of health care.

“The data we were receiving at 8 in the morning was useless by 9 a.m.,” lamented Michaud. “It got to the point [during the pandemic] where I ignored all modeling.” For him and his member hospitals throughout Maine, this data even became “distracting” because the things that were planned based on models were “ultimately nowhere near accurate.”

For Lewis and the Rhode Island hospital association members, it was the surveillance data that was fraught with discrepancies during the pandemic. “Every state public health department has reportable diseases so surveillance procedures were already in place. Yet, there's all of these systems that don't necessarily speak to each other,” she said.

Lewis added: “Throughout COVID, we have really had an unprecedented amount of testing, with testing itself used as a surveillance tool to identify the hot spots within our communities to appropriately target resources. But the main problem with the surveillance tools that exist today is not the ingenuity to come up with new ones, but the inability to allow them to speak to each other so that we can create an overlapping map [of all the data sets].”

The conversation about existing barriers in the field included a robust discussion on health equity and how best to integrate a framework into existing policies and procedures so that when future emergencies occur, considerations for the social determinants of health (SDOH) are already active.

“Take health care to the people when you can,” suggested Lewis, addressing the issue of health equity during a crisis. She added that for those who are “disenfranchised by language and by culture,” COVID-19 has been a very difficult situation. For example, there are geographic barriers to equitable treatment, including directives to go to one place for testing, another for medicine and yet a third place to see a health care provider.

For Bizarro-Thunberg, health equity and SDOHs are directly tied to policy and legislation. “We actually have made some strides in codifying some equitable changes into law. Most notably are the flexibilities for professional licensure, including allowing student nurses to start working before graduation and allowing retired and out-of-state professionals to be licensed [in New Hampshire] more easily. Also, the expansion of telehealth was put into state law.”

The New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services also was able to affect policy changes by utilizing something called a public health incident declaration, which included such opportunities as allowing hospitals to establish temporary acute care centers in their facilities that also had immunity protections, especially during the delta variant surge last winter.

Lastly, in relation to policy, Bizarro-Thunberg pointed out that some changes that were helpful in responding to COVID-19 have been challenged and changed by her state’s legislature, mostly “fueled by misinformation.” She said these include: the governor's powers to declare a state of emergency; the Department of Health and Human Services’ ability to use public health incidents; adding conscientious objection to the approved list of vaccinations exemptions; and a potential bill that will create a standing order for ivermectin to be used to treat COVID-19. The latter is “something that we know clinically is not proven, but we have a lot of legislators who are following misinformation to an illogical conclusion.”

There is hope for lasting and informed changes to policy, Bizarro-Thunberg added. She pointed to programs and coalitions that have “brought together not just hospitals, but education and business groups to the table to try to fight against misinformation that's been happening now.”

The creative convening also highlighted the determination, resiliency and spirit displayed since the pandemic throughout the field. “As tragic as this has been for people that lost their lives, livelihood or loved ones, there are some silver linings,” Michaud acknowledged. “What our members did is not just heartwarming, but it’s hard to believe how well they rose to the occasion. It was a marvel to watch.”

Lewis mentioned another positive, which she described as “the hope and belief emanating from many of our hospitals that they can … not only use these lessons and use these opportunities to be better prepared for another pandemic, but also foster a more thoughtful and healing approach to all aspects of health care.”

This event commenced a series of national and regional discussions that will inform an Emergency Preparedness Field Guide, part of a new, multiyear cooperative agreement with the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR), funded by way of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The project will document many of the stories of perseverance from the last two-and-a-half years of the pandemic to identify opportunities for innovation and change for AHA members and cross-sector partners as well as for patients and communities.

To learn more about the work that the AHA is doing in partnership with ASPR, contact Helena Bonfitto, AHA Senior Program Manager (hbonfitto@aha.org).

Benjamin C. Wise is a senior communications manager at the AHA and serves as a core team member for the funded partnership with ASPR.

Presented as part of Cooperative Agreement, 1 HITEP210047-01-00, funded by the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR). The Health Research and Educational Trust, an AHA 501(c)(3) nonprofit subsidiary, is a proud partner of this Cooperative Agreement. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response (ASPR) or the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).