AHA Comments on CMS’ Proposed Rule on the Increasing Organ Transplant Access (IOTA) Model

February 9, 2026

The Honorable Mehmet Oz, M.D.

Administrator

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

7500 Security Boulevard

Baltimore, MD 21244-1850

Submitted Electronically

RE: CMS–5544–P Medicare Program; Alternative Payment Model Updates and the Increasing Organ Transplant Access (IOTA) Model

Dear Administrator Oz:

On behalf of our nearly 5,000 member hospitals, health systems and other health care organizations; our clinician partners — including more than 270,000 affiliated physicians, 2 million nurses and other caregivers — and the 43,000 health care leaders who belong to our professional membership groups, the American Hospital Association (AHA) appreciates the opportunity to comment on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS’) proposed rule on the Increasing Organ Transplant Access (IOTA) Model.

Our members have long supported the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) in testing innovative payment and service delivery models aimed at improving health care quality and lowering costs. To achieve these goals, it is important to have models that are thoughtfully designed, aligned with their intended objectives and feasible for providers to implement. Accordingly, we have recommended common guiding principles for CMMI to consider when developing new models. However, we remain concerned that the IOTA Model, both as finalized in 2024 and considering the proposals in this rule, does not follow these principles and will not meaningfully advance the transition to value-based care. In fact, several aspects of the IOTA Model’s design may decrease access and adversely affect patients’ quality of care. Thus, to advance our shared goal of increasing access to kidney transplantation, we respectfully suggest changes below.

- The IOTA Model should be voluntary. Hospitals should be able to evaluate whether CMMI models are suitable for their patients and communities. However, IOTA compels mandatory participation by selected hospitals, including those that may not be in a position to invest the resources necessary to be successful in the model or absorb potential losses. The upside risk payments do not adequately cover costs to support the infrastructure necessary to succeed, while the downside risk can result in payment cuts that destabilize programs and may ultimately result in reduced patient access, contrary to the model’s goals.

- The low-volume threshold must be adequate. We appreciate CMS reconsidering the current low-volume threshold based on feedback from participating hospitals. However, the proposal to raise it from 11 to 15 cases remains inadequate. A low-volume threshold should ensure hospitals have enough kidney transplant volume to implement care changes and assess their impact. It should also allow hospitals to offset the infrastructure costs required for model participation and reduce financial risk from outliers and small-sample volatility. If participation continues to be mandatory, we urge CMS to establish a low-volume threshold that ensures statistical significance and minimizes the effects of outliers and case variability.

- CMS should ensure the risk adjustment approach is sufficient. While we are encouraged by the proposal to include risk adjustment when calculating performance on the composite graft survival rate metric, it is unclear whether the proposed methodology is sufficiently constructed and tested to ensure fair and accurate comparisons in performance, as well as consistent with other methodologies standard in the organ transplant field. We urge CMS to provide additional insight into the development of its proposed risk adjustment methodology.

- The upside risk payment should not be reduced. Although we support CMS’ consideration of whether the growing population of Medicare Advantage (MA) enrollees could be included in the model, the agency should proceed with caution before making significant changes during the performance period. If CMS does include MA patients, however, we strongly oppose any decrease in the maximum upside risk payment. Reducing the payment by more than 30% as the agency suggests would render it wholly insufficient to cover a hospital’s costs to participate in the model, let alone incentivize increased access to transplants.

- Certain transparency provisions should not be finalized. The AHA and its members support meaningful transparency, including some of the proposals in this rule, as they represent actions that most — if not all — of our members are already undertaking to keep their patients informed. However, CMS’ proposed updates to the information IOTA participants would be required to make publicly available and actively communicate to eligible waitlist patients are unlikely to achieve the goals of the model. Instead, they would at best add unnecessary administrative burden for providers and increase confusion among patients, potentially sowing distrust in the transplant system. We urge the agency not to finalize them.

Our members remain strongly committed to expanding access to safe, high quality kidney transplantation. However, the IOTA Model as currently constructed falls short of this objective. Accordingly, we maintain that participation in the IOTA Model should not be mandatory. Many of the current model design elements as well as the changes that CMS is proposing run counter to the agency’s commendable goals for the model while increasing administrative burden and costs for participating hospitals.

We appreciate your consideration of these issues. Our detailed comments are attached. Please contact me if you have questions or feel free to have a member of your team contact Robyn Tessin, AHA director of payment policy, at rtessin@aha.org.

Sincerely,

/s/

Ashley Thompson

Senior Vice President

Public Policy Analysis and Development

Cc: Abe Sutton

Director, Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation

Background

The IOTA Model is a six-year mandatory model for certain kidney transplant hospitals that began July 1, 2025. It is designed to test whether performance-based incentives (or penalties) for participating kidney transplant hospitals can increase access to kidney transplants for waitlist patients while preserving or enhancing quality of care and reducing Medicare expenditures. CMS has selected 103 kidney transplant hospitals to participate in the IOTA Model and will measure and assess participants’ performance across three domains: achievement, efficiency and quality. The proposed rule would make changes to the IOTA Model beginning July 1, 2026.

Participant Eligibility

Low-volume Threshold

CMS previously finalized a low-volume threshold requiring a kidney transplant hospital to have performed 11 or more kidney transplants for patients 18 or older annually in each of the three baseline years to be eligible for selection into the IOTA Model. The agency states that it is now reevaluating the current threshold due to concerns expressed by some hospitals regarding their ability to participate. As such, it proposes to raise the low-volume threshold from 11 to 15. The agency alternatively considered and seeks comment on higher thresholds, such as 20 or 25 kidney transplants, but thinks that a threshold of 15 would best balance excluding the smallest kidney transplant hospitals with ensuring the validity of the model. CMS states that the proposal would result in the removal of only one participant hospital as of the model start date, whereas higher thresholds resulting in more participants being removed could diminish its ability to evaluate the model.

We support CMS’ reconsideration of the current low-volume threshold. However, the proposal to raise it from 11 to 15 cases is inadequate. A low-volume threshold should ensure that hospitals have sufficient kidney transplant volume to be able to implement changes in care delivery and evaluate whether those changes have an impact based on statistical significance. Additionally, it should ensure that the infrastructure costs necessary for model participation (such as data analytics and staffing resources) can be offset by potential gains under the model. Financially, it also should protect against outliers and volatility inherent in small sample sizes. A threshold of 15 cases across each of three years fails to meet these criteria. CMS states that it would exclude the smallest kidney transplant hospitals while including a sufficient number of hospitals to ensure a valid model test, yet the agency has neither cited any data nor performed any analysis to support this position. It also has not addressed whether a threshold of 15 would generate an adequate sample size to ensure statistical significance or cited any other reasonable rationale for its proposal. If CMS continues to make participation in the IOTA Model mandatory, we urge it to conduct and publish analyses to determine a threshold that ensures statistical significance and effectively mitigates potential impacts of outliers and volatility in cases.

Military Medical Facilities

CMS selected four Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical facilities and one military medical treatment facility (MTF) for participation in the IOTA Model. However, the agency now states that this was unintended because, by statute, Medicare does not provide coverage or payment for services furnished by a federal provider of services or other federal agency, or services that receive direct or indirect funding from a governmental entity, with limited exceptions. Thus, it proposes to exclude kidney transplant hospitals that are a VA medical facility or a MTF from participating in the model. We support CMS’ proposal and agree that excluding these facilities would more appropriately focus the model evaluation on a subset of hospitals that operate under similar Medicare reimbursement conditions and face comparable regulatory requirements.

Performance Assessment

In previous rulemaking, CMS adopted provisions to assess performance across three domains: achievement, efficiency and quality. In this rule, CMS proposes changes to the quality domain. Specifically, participants are assessed on their composite graft survival rate, defined as the cumulative number of functioning grafts divided by the cumulative number of all kidney transplants performed. In response to concerns from stakeholders, including the AHA, regarding the lack of risk adjustment in the measure, CMS now proposes to adopt a risk-adjustment methodology to account for several transplant recipient and donor characteristics. In addition, the agency proposes to exclude multi-organ transplants (MOT) from the composite graft survival rate.

The AHA appreciates CMS’ response to our concerns and supports the exclusion of MOT from the measure calculation as well as risk adjustment for the quality metric used to assess performance in the model; we believe that these updates would improve the accuracy and fairness of calculation on the composite graft survival rate measure. However, we urge CMS to provide additional insight into the development of their proposed risk-adjustment methodology. Specifically, we are interested in the agency’s rationale behind creating a new methodology rather than deploying the existing Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) post-transplant outcomes models that are already considered the standard for the purpose of risk adjustment. We are concerned that the proposed, novel approach might not capture the full spectrum of variation in risk and might be inconsistent with methodologies used throughout organ transplantation. We suggest that CMS conduct a comparison of the SRTR with its proposed methodology and analyze any key differences to ensure robust risk adjustment.

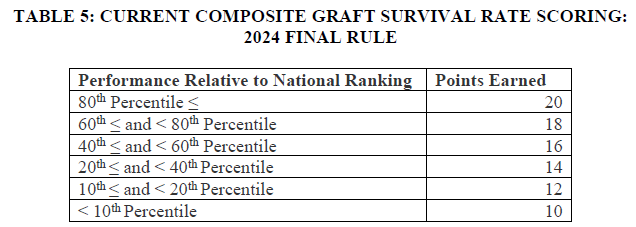

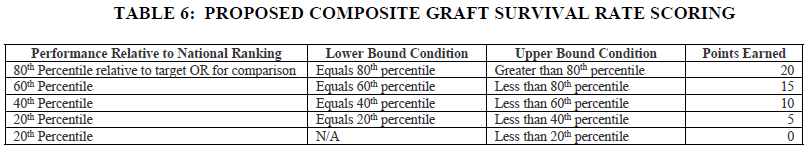

In addition, we question the rationale behind updating the allocation of points awarded for performance on the composite graft survival rate measure. Overall, CMS lowers the minimum number of points that may be earned from 10 to 0. In addition, rather than awarding points to the tiers of performance in bands of two, CMS proposes instead to score participants in bands of five, as seen in the tables below copied from the rule.

This change would result in fewer points for any participant whose performance was below the 80th percentile in comparative composite graft survival rate. For example, in the original scoring, a participant who scored in the 79th percentile of performance would receive 18 points; in the proposed scoring, that same participant would receive only 15 points. While this may appear to be a negligible change, the IOTA Model assesses quality performance solely on this measure. We are concerned that this proposal arbitrarily places outsized importance on a measure that has not yet been validated against existing Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) measures, an issue that is exacerbated because participation in IOTA is mandatory. The AHA opposes this change and urges CMS to develop a more meaningful quality performance assessment methodology.

Payment

The IOTA Model includes upside and downside performance-based payments calculated based on the number of kidney transplants performed for attributed Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries during a performance year. Participants are measured against specified targets in the achievement, efficiency and quality domains, and earn a final performance score between 0 and 100 points. Based on their final performance score, participants may be eligible for upside risk payments of up to $15,000 per case or downside risk payments (owed to CMS) of up to $2,000 per case.

Alternative Payment Design

The model’s two-sided risk payments currently are calculated based on “Medicare kidney transplants,” defined as kidney transplants furnished to attributed patients whose primary or secondary insurance is FFS. CMS seeks comment on whether MA patients also should be included in the calculation of these payments to further the incentive effects of the model and in recognition of the growth of MA enrollment. The agency states that FFS enrollment of the total end-stage renal disease population enrolled in Medicare was around 45 percent in 2024 and is projected to decrease to around 40 percent by 2028. It further states that if MA kidney transplants were to be included in the payment calculation, the number of Medicare kidney transplants performed per hospital would increase on average; as such, the maximum upside risk payment could be lowered from $15,000 to $10,000 per Medicare kidney transplant. CMS projects that these changes to the model would approximately offset each other and have a net zero impact on model savings.

We support CMS’ consideration of how best to structure the incentive effects of the IOTA Model and whether the growing population of MA enrollees could be incorporated therein. However, we urge the agency to proceed with caution before adopting any significant changes to the model design while the performance period is already underway. Historically, the payment and service delivery models implemented by CMMI have been focused on Medicare FFS beneficiaries. While we commend CMMI for seeking to broaden the range of patients in its models, the agency should thoroughly examine the potential effects of such decisions. In particular, CMS should identify and consider any potential unintended consequences for the contracting relationships between providers and MA organizations (MAOs). For example, if MA enrollees are to be included in CMMI models, the agency must ensure that the model design does not create conflicting incentives for providers who contract with MAOs and may be already participating in similar value-based care initiatives pursuant to those contracts.

The agency also should confirm that it would have access to timely and accurate data on the number of MA enrollee kidney transplants for a participating hospital. As the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission has noted, the encounter data that CMS collects from MA plans are critical to the Medicare program, yet the data are incomplete and have limited validation for certain types of encounters.1 CMS should ensure that adding MA enrollee kidney transplants to the performance-based payment formula would not create a new reporting burden that requires hospitals to provide these data to CMS.

In the event that CMS decides to calculate the performance-based payments based on MA as well as FFS patients, the AHA strongly opposes any decrease in the maximum upside risk payment. Even at its current level ($15,000), the maximum amount likely would not cover a hospital’s costs and resources expended to participate in the IOTA Model. These costs and resources include, for example:

- Staff and software to track attributed patients and measure performance, including additional time and resources to track MA enrollees as well as FFS patients.

- Staff and software to support transparency requirements (e.g., maintenance of public websites for reporting information, periodic notifications to each individual attributed patient), as well as extra support to implement the significant expansion of these requirements that CMS is proposing.

- Staff and space to support increased transplant volume. Additional transplant coordinators, clinical staff (including surgeons and nurses), and capital for additional operating room suites may be needed.

If CMS were to decrease the maximum upside risk payment, particularly by more than 30% as the agency suggests, it would be wholly insufficient to cover the costs necessary to successfully participate in the model. Indeed, the payment amount would be below that of the Kidney Care Choices Model, which included a $15,000 bonus, roughly equal to $18,000 today when accounting for inflation. This inadequate incentive payment would effectively function as a penalty for hospitals required to participate in the IOTA Model because it would not cover their costs and would force them to siphon resources away from other clinical care areas. It could also impact workflows for other clinical areas because as multiple service lines utilize a hospital’s operating room suites, there is limited capacity to increase volumes without requiring additional space.

CMS asserts that the number of Medicare kidney transplants performed per hospital would increase on average if MA patients were taken into account, which would allow for a lower maximum upside risk payment. Yet this increase would not be the case for all hospitals participating in the IOTA Model. Indeed, hospitals do not have control over the overall payer mix in their communities (e.g., whether MA is prevalent in their market), and those with a lower-than-average share of MA patients likely would see a net decrease in their expected performance-based payments under the model. And, of course, they would not be able to decline participation in the model due to this penalty that is based on factors beyond their control.

Further, CMS has provided no policy rationale for its choice of $10,000 as the maximum upside risk payment other than backing into a desired savings outcome. For example, it did not analyze why it believes this dollar amount would be adequate to incentivize hospitals to increase access to kidney transplants and improve their performance on model metrics. In fact, to increase the number of transplants it performs, a hospital may have to use more complex organs, which would result in increased costs to the hospital for the transplant surgery and services provided during the post-operative period. A maximum upside risk payment of $10,000 likely would not cover these additional costs or incentivize hospitals to make the necessary investments to succeed under the model.

Decreasing the maximum upside risk payment by more than 30% after the performance period has begun also would undermine hospitals’ significant reliance interests in the model design. Once a hospital has been chosen for mandatory participation in the IOTA Model, it would have to take steps to prepare, which may include implementing care redesign, adjusting its budget to account for the costs of participation, forecasting performance on model measures and estimating its expected net payments under the model. Its decision-making and investment of resources would be predicated on the potential to earn up to a $15,000 bonus per FFS transplant case. Yet CMS is now considering whether to change this figure to a lower amount after the model has begun without taking into account hospitals’ reasonable expectations a higher upside risk payment would continue for the duration of the model.

Finally, changing the payment methodology after testing has begun also would compromise CMS’ ability to evaluate the IOTA Model. The agency is required under section 1115A(b)(4) of the Social Security Act to conduct an evaluation of each CMMI model, including an analysis of the quality of care furnished and changes in spending. However, it did not address in the proposed rule, for the benefit of public comment, how it would account for a change of this magnitude in the model evaluation and whether such a change could affect the validity of the evaluation.

Final Performance Score Ranges

CMS states that it previously finalized for performance years 2 through 6 that an IOTA Model participant would qualify for the neutral zone (meaning it would not receive an upside or downside risk payment) if its final performance score was from 41 to 59 points (inclusive). In response to confusion expressed by IOTA Model participants about final performance scores of 40 and 60 points, CMS proposes to clarify the final performance score thresholds at which participants would qualify for risk payments or the neutral zone. Specifically, the agency proposes that a score above 60 points would qualify a hospital for an upside risk payment, a score from 40 to 60 points (inclusive) would qualify for the neutral zone and a score below 40 points would qualify for a downside risk payment.

We appreciate CMS’ efforts to address confusion concerning the formula for calculating the upside and downside risk payments under 42 C.F.R. § 512.430. Although we agree the formula as currently written needs clarification, we urge CMS to further lower the minimum scores that would qualify for upside risk payments and the neutral zone. Given that the IOTA Model is mandatory for all participants, the potential for upside risk (or at a minimum, neutral risk) should be greater than the potential for downside risk. Indeed, allowing hospitals more opportunity to qualify for upside risk payments would further the incentive effects of the model and better support its goals of increased access to transplants. At the very least, hospitals that have no choice but to participate in the model should be given more latitude to avoid downside risk by lowering the scoring threshold for the neutral zone.

Downside Risk Payment

CMS also proposes to correct a typographical error in the regulation text to clarify that an IOTA Model participant must pay the downside risk payment to CMS in a single payment within 60 days, rather than at least 60 days, after the date on which a demand letter is issued. The agency states that the amount owed would be considered a delinquent debt if not received within that time period and potentially referred to the Department of the Treasury.

We recognize the importance of timely repayment. However, timely upside risk payments to hospitals are also important. As such, we recommend that CMS clarify and commit to an expedient timeframe in which it will make upside risk payments to IOTA Model participants. The regulation text at 42 C.F.R. § 512.430(d)(5) states that after notifying participants of their final performance score and any associated upside risk payment, the agency will issue the payment “by a date determined by CMS.” Hospitals should not be held to a more stringent standard for repayment than the agency holds itself to for upside risk payments. We urge CMS to make these payments as quickly as possible to allow sufficient time for hospitals to budget and invest resources to ensure their successful participation in the model.

Extreme and Uncontrollable Circumstances

CMS previously finalized that for the IOTA Model, it will use determinations made under the Quality Payment Program (QPP) as to whether an extreme and uncontrollable circumstance (EUC) has occurred and the geographic area affected. Based on those determinations, it could then reduce the amount of an IOTA Model participant’s downside risk payment prior to recoupment. However, the agency now states that upon further consideration, QPP determinations may not account for the broader impacts that an EUC might have on a hospital’s ability to perform in the IOTA Model if organ allocation systems are disrupted or disaster conditions disproportionately affect post-transplant outcomes.

As such, CMS proposes to modify its EUC policy for the IOTA Model such that the agency may, at its sole discretion, apply flexibilities if the participant is located in an emergency area during an emergency period for which the Secretary of Health and Human Services has issued a waiver under section 1135 of the Social Security Act and if the participant is located in a county, parish or tribal government designated in a major disaster declaration under the Stafford Act. It also proposes that it would have the sole discretion to determine the time period during which payment and reporting flexibilities are extended, and that it may adjust the direction and the magnitude of the upside or downside risk payments during an emergency period.

We support CMS’ proposal to the extent it would take into account a broader range of extreme and uncontrollable circumstances that could impact a hospital’s performance in the IOTA Model. Indeed, special consideration should be given to circumstances affecting transplant hospitals given the unique nature of care delivery related to transplants, the role of organ allocation systems and potential disproportionate impact on post-transplant outcomes. However, we recommend that CMS not limit its determinations to locations and periods covered by section 1135 waivers and Stafford Act declarations as they do not represent the wide range of circumstances that could adversely affect hospital performance under the model. For example, disruptions to the operations of the OPTN or its contractors (including match runs and allocation decisions), suspension or decertification of Organ Procurement Organizations, and other factors outside of a hospital’s control that cause it to temporarily reduce or suspend its transplant activities all could significantly affect IOTA Model performance separately and apart from declared emergencies or disasters. CMS should modify its policy to allow for participation, reporting and payment flexibilities in the event a hospital experiences any EUC that may adversely affect its performance in the model.

Transparency Requirements

In previous rulemaking, CMS finalized provisions to advance transparency for individuals seeking transplant waitlist access and to improve patient health literacy regarding transplant program evaluation processes. In this rule, CMS proposes several updates to the information that IOTA participants would be required to make publicly available and actively communicate to eligible waitlist patients.

The AHA and its members support meaningful transparency between transplant centers, organ recipients, donors, their families and other stakeholders. We appreciate that CMS is working to increase access to organ transplantation by encouraging efficient sharing of information. The AHA supports some of the transparency proposals in this rule, as they represent actions that most — if not all — of our members already undertake to keep their patients informed. For one, CMS proposes that IOTA participants must review their publicly posted patient waitlist selection criteria annually, and those participants that perform living donor transplants must publicly post on their websites their selection criteria. This information already is readily available from transplant centers, and because CMS does not propose to require use of any standardized selection criteria or templates, this proposal would allow for transplant centers to provide useful information in formats most helpful for their patients and communities. Thus, the AHA supports this proposal.

Other proposals in this section, however, are likely to result in wide-ranging adverse consequences for the organ transplantation environment. In addition to being administratively burdensome for IOTA participants, the nature of the information proposed to be shared and the manner in which CMS proposes IOTA participants communicate with patients on waitlists would result in confusion without any substantive benefit to patients, as described further below.

Notification of Declined Organ Offers

We are extremely concerned about CMS’ proposal to require IOTA participants to notify eligible IOTA waitlist beneficiaries of the number of times an organ is declined on that beneficiary’s behalf at least once every six months that the beneficiary is on the waitlist. While the agency does not currently propose to require explanations for why each organ offer was declined, CMS does seek public comment on whether it should, and the agency enumerates the various other explanatory data elements that a notification would be required to include. The AHA strongly opposes this proposal because the administrative complexity of implementing it would far outweigh its potential value to either patients or providers.

CMS originally proposed similar provisions in previous IOTA rules but declined to finalize them in response to the many concerns received via public comment. The AHA maintains our same concerns with the proposals in this rule as we had in the past. For example, the processes necessary to generate these notifications would be extremely onerous, likely necessitating hiring additional staff for compliance. This is, in part, because there is no singular file of waitlist patients that a transplant center can simply download and easily populate with the various elements that would be required; pulling together this information would be a manual process done on a patient-by-patient basis that could take weeks — or even longer for larger transplant centers.

We acknowledge that if the notifications provided meaningful information, such a burden might be worthwhile. However, this is not the case. The heavily clinical content of the notifications as proposed likely would be difficult for the average waitlist patient to understand. If the notifications were delivered automatically (that is, not upon request or following an interaction with the transplant team), a patient would likely be caught off guard. The resulting confusion and surprise could interfere in the relationship between the transplant team and the patient, lessening trust and damaging communications. Indeed, transplant teams already have extensive discussions with patients about reasons for declining an organ on their behalf. These clinical decisions are based on a holistic assessment of whether an organ is suitable for transplant for that particular patient and may not be easily boiled down to one or even multiple factors in isolation. Rather, it is based on the clinician’s judgment of all factors, along with their ongoing discussions with patients about their goals and wishes.

To that point, elements that would be required for inclusion in the notifications are the number of times a waitlist beneficiary appears on a match-run and the number of donors from whom organ offers were generated. However, transplant candidates may appear on hundreds of match-runs prior to transplant, especially if they are low in priority based on their time on the waitlist. A notification of the number of times they appear on a list is unlikely to provide useful information; worse, this information might prove needlessly disheartening and cause beneficiaries to question why they are (appropriately) not receiving organs despite numerous match-run appearances. Once again, this proposal could erode the trust between waitlist beneficiary and transplant team by sowing uncertainty.

Another required element is the reason(s) why offers were declined based on OPTN refusal codes in plain language. However, the refusal reason codes are clinically technical, and there often are not “plain language” ways to explain them. For example, Code 713 states “warm ischemic time too long.” Explaining what this means to an individual without high medical literacy would not only be a challenge but also could raise more questions than it would answer. Notifications also would be required to include the number of kidneys transplanted in other kidney transplant patients out of all the deceased donor kidney organ offers declined for that eligible IOTA waitlist beneficiary. In practice, it is infeasible to inform a recipient candidate regarding the outcome of a transplant performed at another center after being declined.

Change in Waitlist Status

Transplant hospitals are required to notify patients when they are first added to or removed from a waitlist. In this rule, CMS proposes to require IOTA participants also to notify their eligible waitlist patients who are Medicare beneficiaries when their waitlist status has changed from active to inactive, as well as the reason for the change in waitlist status and how the patient may become active again (e.g., by updating personal information or providing new clinical data). Participants would have to provide this notification to the beneficiary electronically or by mail within 10 days of the change in waitlist status and annually thereafter.

Transplant centers generally have their own internal systems for maintaining up-to-date waitlists and communicating changes in status with transplant candidates. These systems are more nuanced than the binary active/inactive status updates proposed in this rule. For example, most programs have an additional “interim” status that acts as a temporary internal hold that does not affect a waitlist patient’s “official” status but nonetheless indicates their readiness for an organ. A patient may be on this “interim” status if they were on short-term antibiotics following a dental procedure, or if they planned to be out of the country and thus would be temporarily unavailable to receive an organ. Further, transplant centers provide these updates to all patients, regardless of payer. Therefore, the proposal in this rule is far narrower than what our members are already doing and could serve to create divergent methods of communication based on waitlist patient payer source. Because of these disadvantages, the AHA does not believe the proposal will achieve its purported aims and encourages the agency not to finalize it.

In CMS’ explanation of why the agency decided against proposing that IOTA participants also notify eligible waitlist patients when their status changes from inactive to active, it cites the “significant administrative burden on IOTA participants, particularly IOTA participants with limited resources, requiring substantial investments in new systems and staff time that could divert resources from direct patient care.” In addition, CMS reasons that “frequent status change notifications might create patient anxiety and unrealistic expectations about organ offer immediacy, potentially overwhelming clinical teams and undermining transparency goals, while standardized requirements may fail to account for diverse patient populations with varying literacy levels and communication needs.” The AHA agrees with this reasoning and, indeed, it applies to what CMS is proposing to require in terms of waitlist status notifications as well. In other words, uniform, boilerplate notifications of change in waitlist status (either from active to inactive or vice versa) alone are unlikely to improve transparency and patient empowerment. Rather, transplant centers should be supported in continuing to provide real-time, personalized communication that delivers meaningful and actionable information to patients.

________________________

1 https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/MA-encounter-data_FINAL.pdf