Proposals to Reduce Medicare Payments Would Jeopardize Access to Essential Care and Services for Patients

A review of the evidence and the negative impact site-neutral payment policies have on the ability of hospitals and health systems to care for patients and communities

Key Highlights

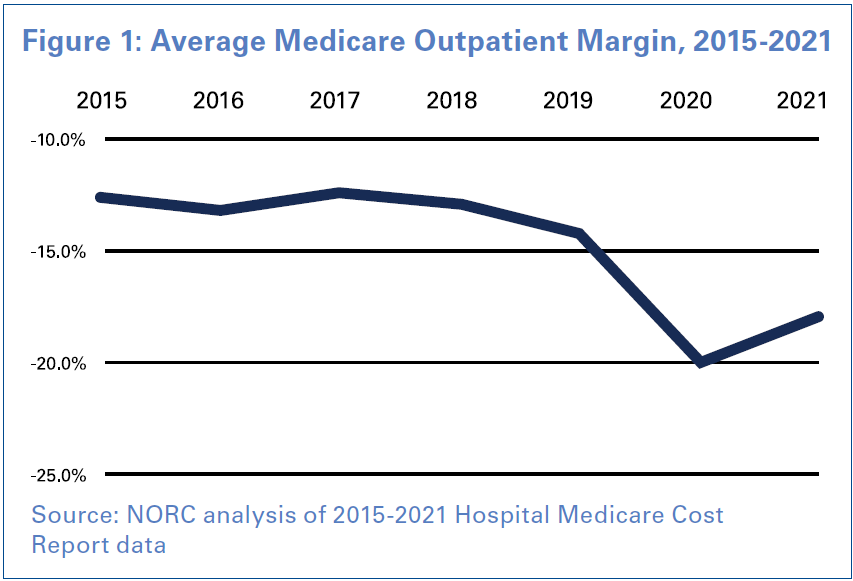

- Medicare significantly underpays hospitals for the cost of caring for patients. Medicare outpatient margins were an average of negative 17.5% in 2021 alone. Site-neutral payment policies would further deepen these underpayments.

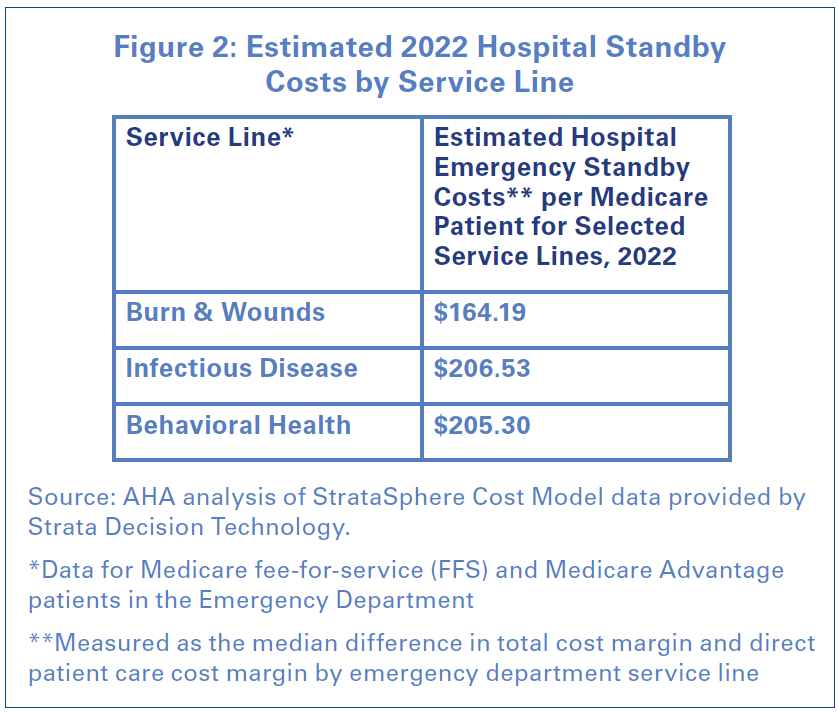

- Site-neutral policies ignore important differences between hospital outpatient departments and other outpatient care settings. Hospital outpatient departments are required to comply with many more regulatory and safety codes than other care settings and provide 24/7 standby capacity for emergencies. These costs can amount to over $200 per patient, resulting in hospitals losing money when providing certain services.

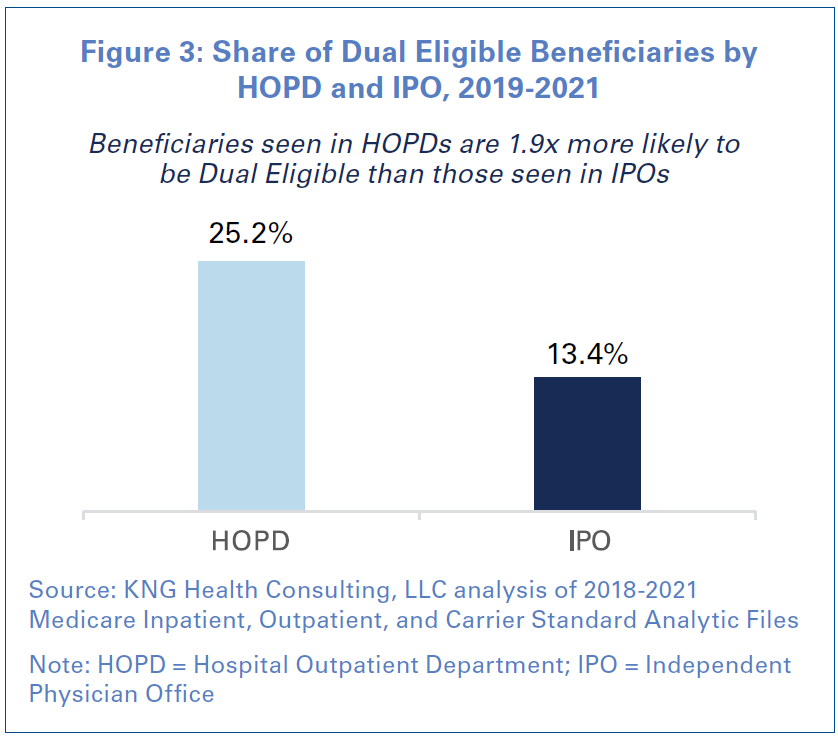

- Hospital outpatient departments care for sicker and more complex patients than other outpatient care settings. They also are twice as likely to provide care to patients who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid.

- Site-neutral policies are based on the flawed assumption that Medicare payment rates to physicians are sustainable for all providers. The severe underpayments to physicians are forcing many of them to turn to hospitals and health systems for financial security, with 94% of physicians saying that operating a practice is financially and administratively challenging.

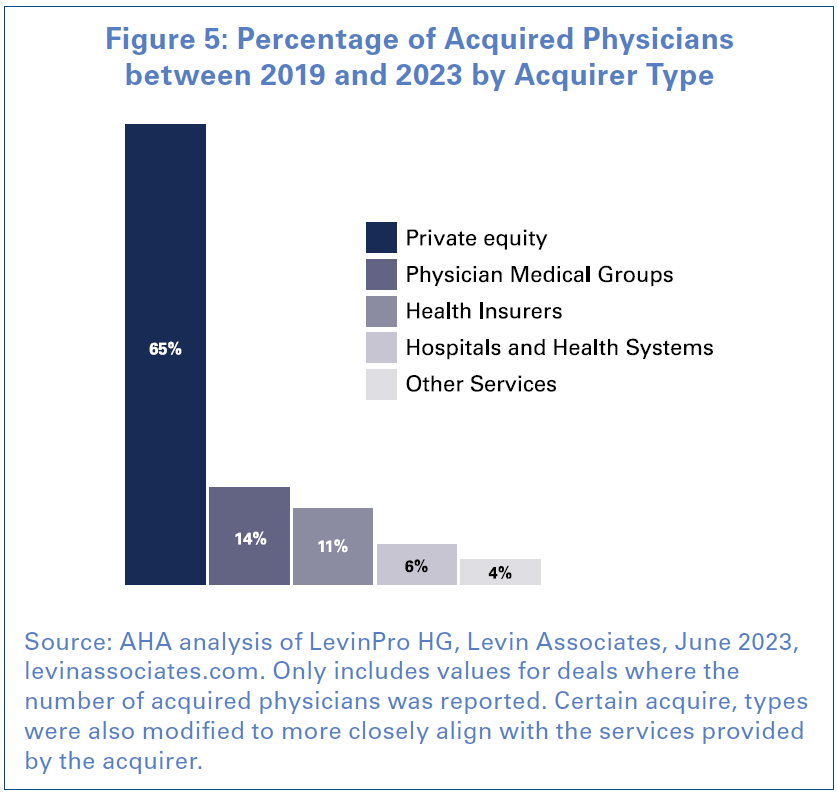

- The scrutiny of hospital acquisitions of physician offices is misplaced as hospitals are not the primary acquirers of physician practices. Over the last five years, private equity entities account for the vast majority of physician acquisition deals and those deals have involved the largest number of individual physician providers. Insurance companies like UnitedHealthcare and Humana also are bigger acquirers of physician practices than hospitals.

- Legislative proposals that seek to expand site-neutral policies would further increase Medicare underpayments to hospitals by billions of dollars and jeopardize access to care for patients across the country.

Introduction

Site-neutral payment is a misguided policy that seeks to further align provider payments among care settings. However, these policies disregard a patient’s acuity, the complexity of care, and the regulatory requirements that exist among different settings. In most cases, the term “site-neutral payments” has come to mean reducing payments to hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) by aligning their payment rates with those paid to physicians and ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs). The impetus for these proposals is largely an erroneous assumption that hospitals are overpaid for outpatient services by the Medicare program. In fact, the opposite is true.

Indeed, the federal government significantly underpays hospitals for outpatient services, resulting in consistent negative Medicare margins – a staggering negative 17.5% in 2021, for example. In addition, hospitals and their HOPDs are, by design, markedly different care settings that serve a different purpose for patients and communities than independent physician offices (IPOs) or ASCs. For example, unlike IPOs and ASCs, hospitals are open 24/7, providing care to anyone who comes through their doors, particularly the sickest and most clinically complex patients. As a result, HOPDs, which serve as extensions of the main hospital, are better able to serve their patients by providing seamless access to 24/7 care at the main hospital. In addition, hospitals’ and HOPDs’ safety-net role means they are subject to many regulatory requirements that are not mandated for IPOs and ASCs.

Site-neutral payments began with the passage of Section 603 of the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015. The Act required that services furnished at off-campus HOPDs that bill under the outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS) on or after Nov. 2, 2015 (collectively referred to as “non-exempted” or “non-grandfathered” services) were to be paid under an alternative Medicare outpatient payment system. Since 2018, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has “neutralized” payments for those “non-grandfathered” services by cutting their payment by 60%, mirroring the rate paid to physicians. In 2021, this reduced payment rate was expanded to also apply to clinic visit services at “exempted” or “grandfathered” HOPDs. Despite these existing policies, which take a substantial toll on hospitals’ ability to care for their patients and communities, stakeholders such as the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) have called for additional site-neutral payment policies. Recent proposals by MedPAC and Congress have sought to expand siteneutral payment policies over the next decade by significantly reducing hospital payments at additional sites and for additional services such as drug administration.

This report provides key evidence as to why site-neutral payment policies are misguided, highlighting the substantial negative impact these policies and new legislative proposals would have on access to the care that the nation’s hospitals and health systems provide. In addition, the report shares data that demonstrate important differences between hospitals and their HOPDs compared to ASCs and IPOs.

The Impact of Site-Neutral Payment Policies

To fully understand and contextualize the devastating impact site-neutral payment proposals will have on access to hospital and health system care, it is important to know that Medicare already fails to cover the cost of beneficiary hospital care. Indeed, the latest analysis shows that on average Medicare pays only 84 cents for every dollar of hospital care provided to Medicare beneficiaries. In addition, there is wide variation by state and locality, with some areas of the country experiencing even more loss. While the magnitude of these shortfalls is extremely troubling, perhaps more alarming is the fact that Medicare payments have failed to cover the cost of hospital care for over two decades. And, recent inflation has made the problem even worse. Between 2019 and 2022, Medicare payment rates for hospital outpatient care rose 7.2%, while total hospital costs increased at more than double that, at 17.5%. This has in large part contributed to combined underpayments from Medicare and Medicaid totaling $100.4 billion in 2020 alone.

Unsurprisingly, these gross underpayments have consistently left hospital margins deep in the red. Hospitals’ average Medicare outpatient margins have significantly declined since 2015, with the latest data from 2021 showing Medicare outpatient margins at a staggering negative 17.5% (See Figure 1). The impact is perhaps even more acute for rural hospitals whose total Medicare margins were negative 17.8% in 2021. This is particularly alarming given the fact that 152 rural hospitals have closed or converted to another type of provider since 2010, with 11 occurring so far in 2023.

Unsurprisingly, these gross underpayments have consistently left hospital margins deep in the red. Hospitals’ average Medicare outpatient margins have significantly declined since 2015, with the latest data from 2021 showing Medicare outpatient margins at a staggering negative 17.5% (See Figure 1). The impact is perhaps even more acute for rural hospitals whose total Medicare margins were negative 17.8% in 2021. This is particularly alarming given the fact that 152 rural hospitals have closed or converted to another type of provider since 2010, with 11 occurring so far in 2023.

Additional site-neutral payment policies will only worsen the problem, leaving hospitals no choice but to either close or further curtail services, creating serious access to care issues for communities across the country.

Despite the unworkable situation these policies have already put hospitals and their patients in, three recent congressional site-neutral payment proposals would enact even more substantial cuts to hospitals, and therefore to access to care as well:

- Off-campus Reduction for Grandfathered Drug Administration Services (included in H.R. 3281, Transparent PRICE Act, passed by the House Energy and Commerce Committee): Starting in 2025, and phased in over four years, drug administration services furnished in offcampus provider-based departments (PBDs) would be paid at a site-neutral rate. This proposal would result in a cut to hospitals of $54.2 million in the first year and $3 billion over 10 years.

- Off-campus Reduction for Grandfathered Non-Evaluation and Management (E&M) Services: Starting in 2025, all services (other than E&M services, which are already paid at a site-neutral rate) furnished in grandfathered off-campus HOPDs, including those which are currently exempted from site-neutral payment, such as off-campus emergency departments, approved “mid-build” HOPDs and those in dedicated cancer centers, would also be subject to site-neutral payment. This proposal would result in a cut to hospitals of $2 billion in the first year and $31.2 billion over 10 years.

- All HOPDs MedPAC Site-neutral Proposal: Starting in 2026, site-neutral payments would be made for certain categories of services across ambulatory settings — including HOPDs (both on campus and off-campus), ASCs and IPOs. The site-neutral payment rate that would apply to the services in each ambulatory payment classification would be based on the Medicare payment system for the ambulatory setting in which these services are most commonly furnished. This proposal would result in a cut to hospitals of $11.6 billion in the first year and $180.6 billion over 10 years.

Key Differences and Trends for Hospitals Compared with ASCs and IPOs

Hospitals are designed to care for any patient who comes through the door. They are dedicated to providing patients with a wide range of services, including those requiring intensive and complex clinical care. As such, among Medicare beneficiaries, patients treated in ASCs and IPOs are more likely to be lower acuity and require less complex care. And in instances where patient care requires more complex treatment or becomes emergent, it is safer for these patients to be referred to HOPDs or transported to the nearest hospital for care.

Hospitals are designed to care for any patient who comes through the door. They are dedicated to providing patients with a wide range of services, including those requiring intensive and complex clinical care. As such, among Medicare beneficiaries, patients treated in ASCs and IPOs are more likely to be lower acuity and require less complex care. And in instances where patient care requires more complex treatment or becomes emergent, it is safer for these patients to be referred to HOPDs or transported to the nearest hospital for care.

Differences in Regulatory Requirements

One of the key differences for HOPDs compared with ASCs and IPOs are the range of regulatory requirements that are mandated for each of these care settings. Because HOPDs are extensions of the main hospital, they are held to higher standards than other outpatient care settings. For example, hospitals, unlike ASCs and IPOs, provide and maintain vital services to protect their communities, including:

- 24/7 standby capacity for emergencies, disasters and other traumatic events;

- Special service capabilities such as burn, neonatal, psychiatric services, etc.;

- Uncompensated care and serve as safety-net providers; and

- Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) standards.

In addition, HOPDs must comply with more stringent life safety codes, essential electrical systems, Medicare conditions of participation, as well as strict Joint Commission standards. For example, hospitals and their HOPDs are required to implement violence prevention standards that mitigate violence against health care workers as part of their Joint Commission certification. Importantly, hospitals and HOPDs receive no funding to maintain compliance with all these requirements. Instead, they cover the significant costs of these requirements through their direct patient care revenues. In fact, an AHA estimate of these costs found that these costs can be signficant. An analysis of hospital emergency department data from Strata Decision Technology found that these additional costs can amount to over $200 per patient for some service lines (See Figure 2). As a result, hospitals actually lose money when providing these services to their patients.

Differences in Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Differences in Patient Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

A recent study of Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) claims data by KNG Health Consulting found that compared to both ASCs and IPOs, HOPDs were more likely to provide care to patients who were:

- lower-income;

- non-white;

- eligible for Medicare due to endstage renal disease or disability;

- burdened with on average more chronic conditions and major chronic conditions;

- dually-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (See Figure 3); and

- have experienced a prior emergency room or inpatient hospital stay.

In addition, the study found that these same trends held true even when looking at a specific cohort of Medicare beneficiaries, such as those beneficiaries receiving cancer care. Another important difference was the fact that patients at HOPDs were on average sicker (as measured by the Charlson Comorbidity Index) than patients at IPOs. Taken together, these data highlight the fact that hospitals and HOPDs care for a vastly different population that requires more intensive and complex care.

Differences in Care Provided During a State of Emergency

Differences in Care Provided During a State of Emergency

One of the primary missions of hospitals is to respond to both national and local emergencies. Doing so requires sufficient resources, workforces and coordinated responses with local authorities like the public health agency and law enforcement. Because of their critical role in responding to emergencies such as natural disasters and pandemics, hospitals and HOPDs put significant resources — financial, workforce and technology — toward ensuring they are always prepared and ready to care. This includes supply chain infrastructure, preparedness planning and testing, interagency cooperation and investments in alternative technology and resources in the event of significant infrastructure disruption. In an emergency, communities come to rely on their local hospital’s response to ensure public safety and access to care when often no other community resources are available.

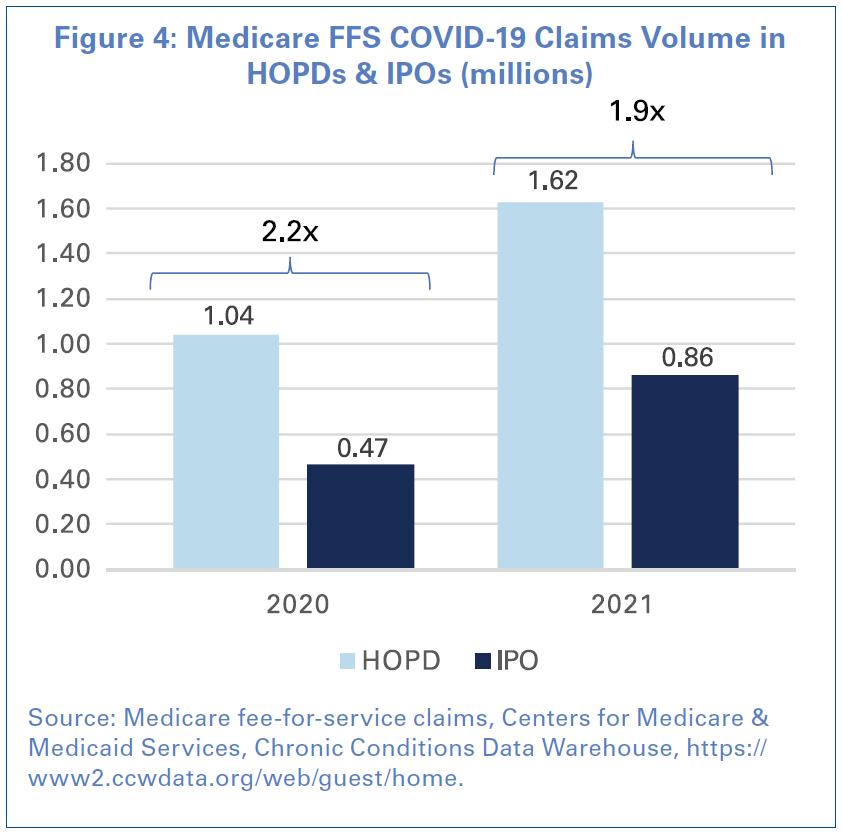

The COVID-19 pandemic nationally spotlighted this care responsibility and community mission. During the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals and their staff experienced multiple surges of patients suffering from the virus, many of whom required intensive care. That level of care and patient surge preparedness was not available at ASCs or IPOs, meaning hospitals and HOPDs were the primary provider of COVID-19 care for the community.

An AHA analysis of Medicare beneficiary claims, who comprised a majority of COVID-19 cases, found that HOPDs had over double the number of COVID-19 claims as IPOs in 2020 and 1.9x the number of claims in 2021 (See Figure 4). This trend is a reversal of typical trends in claim volume. For example, across all Medicare claims, IPOs had approximately 42% more claims than at HOPDs in both 2020 and 2021. The same ratios held true even looking at counts of unique beneficiaries. These findings underscore the critical role that hospitals play in their communities and shows that HOPDs provided more patient care and access than IPOs and ASCs during the COVID-19 public health emergency.

Changes in Physician Practice Preferences

Site-neutral policies are based on the flawed assumption that the Medicare payment rates for physicians are sustainable. However, the facts are much different. When hospitals acquire independent physician practices, it often occurs because the physicians have reached a tipping point — their practices are failing due to poor payer mix, increasing Medicare and Medicaid regulatory burden, and declines in Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement. Instead of allowing these physician services to be lost to the community, or in communities where there are already health care deserts, hospitals acquire the practices to ensure continued access to these services and that patients can continue to receive their care from their existing doctors.

Some groups have suggested that hospitals are acquiring off-campus physician practices so that the hospital can “flip the sign” and receive a higher Medicare reimbursement for providing a similar service. However, this is a deliberate misrepresentation of the facts. Under current law, any off-campus HOPD that was not billing Medicare before November 2015 is no longer paid at the hospital outpatient prospective payment system rate. Instead, this HOPD is already paid at a site-neutral rate under the Medicare physician fee schedule (PFS) for nearly all services it furnishes.

Evidence demonstrates that physicians are increasingly turning to hospitals and health systems for financial security, as well as improved work-life balance, eschewing the administrative burdens and cost concerns of managing their own practice. The administrative and regulatory burden associated with commercial public and private insurer policies and practices, coupled with inadequate reimbursement rates, are barriers to operating an IPO. A survey by Morning Consult on behalf of the AHA found an overwhelming majority (94%) of physicians think it has become more financially and administratively difficult to operate a practice. Managing a physician practice includes costs associated with maintaining electronic health records and patient portals, billing and claim submissions, as well as hiring staff to pursue prior authorization, office rent and other expenses. Collectively, these expenses can present a significant challenge, especially when these costs are met with inadequate reimbursement. Medicare physician payment has effectively been cut 26%, adjusted for inflation, from 2001 to 2023, according to the American Medical Association. Therefore, as IPOs become less financially viable, hospitals are left to care for their patients. This in turn increases hospitals’ costs, making policies like site-neutral payments illogical.

Additionally, the scrutiny placed on hospital and health system acquisition of physician practices is outsized relative to how often it occurs, and how many providers are included in these transactions. Over the last five years, private equity entities account for the vast majority of deals where an IPO is being acquired, as well as the largest number of individual providers that are a part of the deal according to an AHA analysis of Levin Associates data (See Figure 5). Other physician groups are the second largest acquirer. Health insurers were the third largest acquirer of IPOs. However, the size of these acquisitions - both in terms of the average number of providers and the average dollar value of the deals - was larger than all other types of acquirers. Additionally, the average deal price was 762% larger for health insurers than for hospitals. It also is important to note that when other entities acquire physician practices, like private equity firms, they are not obligated to provide care for Medicare and Medicaid patients, while hospital-acquired practices are required to do so.

Additionally, the scrutiny placed on hospital and health system acquisition of physician practices is outsized relative to how often it occurs, and how many providers are included in these transactions. Over the last five years, private equity entities account for the vast majority of deals where an IPO is being acquired, as well as the largest number of individual providers that are a part of the deal according to an AHA analysis of Levin Associates data (See Figure 5). Other physician groups are the second largest acquirer. Health insurers were the third largest acquirer of IPOs. However, the size of these acquisitions - both in terms of the average number of providers and the average dollar value of the deals - was larger than all other types of acquirers. Additionally, the average deal price was 762% larger for health insurers than for hospitals. It also is important to note that when other entities acquire physician practices, like private equity firms, they are not obligated to provide care for Medicare and Medicaid patients, while hospital-acquired practices are required to do so.

Conclusion

Hospitals and health systems across the country continue to experience significant financial and access challenges. Longstanding workforce shortages exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic coupled with skyrocketing expenses driven by rising inflation for labor and drugs to medical supplies and equipment have given rise to an unsustainable environment. Additionally, data show that patients are sicker, requiring more complex care and staying in the hospital for longer periods of time. These realities make policies like site-neutral payments that seek to further cut hospital payments untenable and unwise. Yet, policymakers and other stakeholders continue to push site-neutral payments as some sort of panacea to curb health care costs, when the reality is that they will only serve to further undermine access to care and threaten the financial stability of a critical component of the nation’s health care infrastructure — hospitals and health systems. Furthermore, these proposals to cut hospital payments come on top of existing hospital payment cuts like Medicare sequestration and disproportionate share payment cuts, as well as multiple state-level proposals to cut hospital spending. Taken together, these proposals deepen existing financial challenges for hospitals and health systems, diminish their ability to invest in new technologies and cutting-edge treatments, and undermine access to care. Therefore, we urge Congress and other stakeholders to abandon attempts to enact these misguided site-neutral payment policies and instead focus their efforts on supporting hospitals so that they can continue their mission of advancing the health and well-being of the patients and communities they serve.