New Study: Physician-owned Hospitals Threaten Patient Access and Financial Viability of Full-service Sole Community Hospitals

The challenges facing rural health are well documented — dwindling access to care, sharply shifting demographics, and persistent struggles to recruit and retain a skilled workforce. With nearly half of all rural hospitals operating with negative margins, it's more critical than ever for policymakers to find solutions and advance policies that protect and support rural access to care. However, new legislation introduced in Congress would remove current restrictions on the establishment of physician-owned hospitals (POHs) in rural areas, and it is critical that policymakers understand the negative impact this legislation would have on patients and communities.

It is well established that POHs — arrangements in which physicians can refer their healthiest, best-insured patients to hospitals they own — lead to overutilization and higher costs. Previous analysis has also shown that POHs report on fewer quality measures and have higher readmission measure penalties. Compared to full-service hospitals, POHs are limited in the scope of services offered, often specializing in one type of care, like cardiac or orthopedic surgery, and treating patient populations that are younger, more likely to be commercially insured, and present with less complex conditions. Unlike full-service community hospitals, POHs are not required to provide emergency care, and they often do not. In fact, in many POHs, when a patient needs emergency services, staff call 9-1-1 and send the patient to a full-service hospital for care.

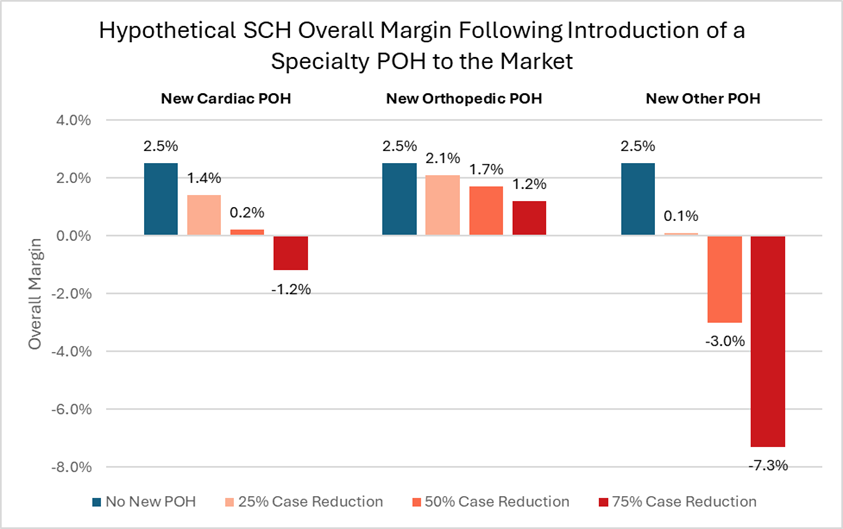

Results from a new Dobson | DaVanzo study further support retaining the ban on new POHs and explain the damage of expanding POHs in rural communities. It demonstrates that should a POH open in the same market as a full-service rural hospital, the full-service hospital’s margins would decrease significantly as the POH siphons off healthier and better-insured patients. Specifically, the report finds that:

- The entry of a new orthopedic POH could reduce the margin of an average sole community hospital (SCH) by more than half (1.2%).

- The introduction of a new cardiac POH could lower overall SCH margins to negative 1.2% — pushing the hospital fully into the red.

- The introduction of a new “other” POH, meaning either another specialty care or general POH, could reduce overall SCH margins to an unsustainably low negative 7.3%.

- SCHs’ overall margins are highly sensitive to the magnitude of volume loss due to the POH self-referral practices, with greater reduction in case volume leading to negative overall and Medicare margins in most scenarios.

Full-service hospitals across the country are struggling, and rural hospitals are particularly vulnerable to headwinds, including staffing shortages, low patient volumes and heavy reliance on payers that reimburse below the cost of care. When their margins decline significantly, rural hospitals are forced to make incredibly difficult decisions — removing services, shuttering departments, laying off staff or closing their doors entirely. The resulting impacts? Communities lose access and jobs, and patients must travel farther for care.

Removing restrictions on POHs, which are notorious for selectively picking the healthiest and wealthiest patients, and allowing them to open near full-service rural hospitals will jeopardize access to 24/7 care in rural America. This new report adds to the overwhelming body of evidence that led Congress to enact a ban on new POHs 15 years ago. Congress cannot forget the dangers POHs pose to high-quality, 24/7 patient care for all.