AHA Comments to the CMS Urging Changes to MA Prior Authorization Requirements for Public Health Emergencies

March 7, 2022

The Honorable Chiquita Brooks-LaSure

Administrator

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services

7500 Security Blvd

Baltimore, MD 21244

Re: CMS 4192-P, Medicare Program; Contract Year 2023 Policy and Technical Changes to the Medicare Advantage and Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit Program

Dear Administrator Brooks-LaSure:

On behalf of our nearly 5,000 member hospitals, health systems and other health care organizations and our clinician partners — including more than 270,000 affiliated physicians, two million nurses and other caregivers — and the 43,000 health care leaders who belong to our professional membership groups, the American Hospital Association (AHA) appreciates the opportunity to comment on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS) proposed rule for policy and technical changes to the Medicare Advantage (MA) program in Contract Year 2023.

The AHA is pleased to provide comments in response to the requests for information regarding prior authorization for hospital transfer to post-acute settings during public health emergencies (PHEs), as well as regarding building behavioral health specialties within MA networks. We also support the series of proposed updates intended to strengthen consumer protections and oversight of MA plans, which we believe will improve access to care for MA beneficiaries.

The AHA particularly appreciates CMS’s interest in learning more about concerns with health plan prior authorization requirements during the pandemic, especially as it relates to the experience of patients referred by general acute-care hospitals to downstream post-acute care (PAC) providers. While the flexibilities CMS offered for MA plans to relax or waive prior authorization requirements during the pandemic were critical for many hospitals and health systems in aiding the COVID-19 response, a substantial limitation of this flexibility is that it encouraged, but did not mandate, that plans waive such processes. While many plans worked collaboratively with provider partners to waive or relax onerous prior authorization requirements during the PHE, others did not, or only did so during the initial stages. The continued use of prior authorization and other health plan utilization management policies by some plans throughout the pandemic exacerbated capacity issues, caused delays affecting patient care and resulted in high rates of inappropriate denials, which we elaborate on in our comments below. As a result, we encourage CMS, working with Congress as necessary, to require plans to waive these administrative processes during PHEs.

The AHA also appreciates CMS’s focus on opportunities to address access issues to behavioral health services in MA. Inadequate behavioral health networks are a pervasive problem in MA plan coverage, and often result in delays in care and direct patient harm. These issues are compounded by administrative barriers and health plan benefit structures that do not appropriately support timely access to behavioral health services. We enumerate the many issues and concerns regarding access to appropriate behavioral health specialties in our full comments below and believe MA plans should be held accountable for ensuring appropriate access to these critical services as required. In addition, we recommend that CMS collect and publicly display data that indicate the adequacy of MA coverage for behavioral health care. Greater transparency in this area would shed light on the specific needs of MA enrollees seeking behavioral health services and help identify opportunities for ensuring the availability of these services.

Our comprehensive comments follow.

CONSUMER PROTECTION AND HEALTH PLAN OVERSIGHT

The AHA is increasingly concerned about MA plan policies that restrict or delay patient access to care, which add cost and burden to the health care system. These policies are harmful to both MA enrollees as well as their providers. Indeed, administrative burden is a substantial contributor to health care worker burn out. We elaborate on some of the most concerning health plan practices in our responses to the requests for information that follow. It is worth noting that while CMS explicitly solicits input on prior authorization in the context of PHEs, hospitals’ and health systems’ deep concerns about the impact of such processes on patient care and health outcomes, as well as the workforce, predate the COVID-19 PHE and, absent further action, will persist once the PHE is over.

Therefore, the AHA supports the proposed updates intended to strengthen consumer protections and oversight of MA plans, which we believe will improve access to care for MA beneficiaries. We commend CMS on its efforts to ensure that MA plans are held accountable for demonstrating that they meet network adequacy requirements (§422.116), as well as other special requirements during a disaster or emergency that are intended to ensure patient access to services (§422.100(m)). We also believe that strengthening the mechanisms to evaluate plan performance when considering applications to enter into a MA contract or expand service areas (such as considering star ratings history, bankruptcy proceedings, and other compliance actions) will help ensure that plans are more accountable for past violations of CMS rules (§422.502 and 422.503). In addition, reinstating more detailed Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) reporting will help to improve public transparency about plan expenditures and profits and to better assess the accuracy of plan MLR submissions (§422.2460, 422.2490, and 423.2460). We also support other provisions designed to protect patients and ensure that plans provide culturally and linguistically appropriate communication with beneficiaries (§422.2260 and 423.2260; 422.2267 and 423.2267; 422.2274 and 423.2267).

Finally, we support the proposed changes to the methodology for calculating the maximum out-of-pocket (MOOP) limit for MA plans to require all costs for Medicare Parts A and B services contracted under the plan to be counted towards the limit (§422.100 and 422.101). We believe that these changes are important consumer protections, and will help to achieve CMS’ stated goals of ensuring more equal treatment of dually eligible MA enrollees and Medicare-only MA enrollees under the MOOP limit.

REQUEST FOR INFORMATION ON PRIOR AUTHORIZATION FOR HOSPITAL TRANSFERS TO POST-ACUTE CARE SETTINGS DURING A PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY

To best care for their communities during the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals, health systems and their partners across the continuum of care needed to quickly turn over general acute-care hospital beds and create space for higher-need COVID-19 patients while ensuring access to the appropriate level of care for those recovering from the virus. This necessitated urgent modifications to traditional discharge processes and hospital-to-PAC clinical pathways to optimize personnel, physical plant and other resources. The flexibilities offered by CMS to relax or waive prior authorization requirements for Medicare Advantage (MA) plans, when implemented, were invaluable for hospitals and health systems in applying these modifications.

However, as noted above, plans were not required to extend this flexibility, and the continued use of prior authorization by many plans throughout the pandemic has prevented referring hospitals from utilizing desperately needed health system capacity in PAC settings. This has been especially problematic when general acute-care hospital beds have been filled to capacity and while healthcare providers contend with the demands of vaccine distribution and workforce shortages. The absence of prior authorization waivers also resulted in unintended consequences for patients who were then forced to stay in acute care settings unnecessarily while waiting for health plan administrative processes to authorize the next steps of their care. During the latter and current stages of the pandemic, full prior authorization policies have largely been reinstated — even in actively surging areas — and AHA members continue to report substantial discharge delays for patients deemed clinically suitable for transfer to a PAC setting.

We recognize that prior authorization is a tool that, when used appropriately, can help align patients’ care with their health plan benefit structure and facilitate compliance with clinical best practices. However, its misuse and application during a PHE has negatively affected patient care and the delivery system’s response to a global health crisis, as described below. Continued flexibility and adoption of prior authorization waivers by MA plans would materially improve pandemic responses across the country.

General Acute-Care Hospitals’ PHE Capacity Needs to Be Augmented by PAC

PAC facilities have played a critical role in the nation’s pandemic response alongside general acute-care hospitals and other healthcare providers by providing highly specialized care to patients with, or recovering from, COVID-19, and supporting the national effort to expand general acute-care bed capacity in response to the emergency.

However, health plan prior authorization policies often disrupted this critical collaboration in the hospital-to-PAC clinical pathway. For example, during the pandemic, some general acute-care hospital patients could wholly or in part receive clinically-appropriate care in another setting, such as a long-term care hospital (LTCH), inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF), or skilled nursing facility (SNF). However, prior authorization requirements frequently delayed or prevented discharge in these cases, requiring general acute-care hospitals to allocate clinical resources to manage patients who could otherwise be safely discharged. Utilization of PAC settings is a critical component of the health system’s necessary response to a PHE. Health plan administrative processes should not supersede the imperative to free up general acute-care hospital capacity and facilitate patient transfers to other settings where clinically appropriate.

Inconsistent Use of Prior Authorization Waivers during the PHE

As noted above, many health plans did not opt to relax or waive prior authorization requirements, or only did so during the initial stages of the pandemic. Some prior authorization waivers for PAC services offered during the initial stages of the pandemic expired around July 2020 and were never reinstated. During the Delta surge, a small portion of plans reinstated waivers, but often for brief periods ranging from 48 hours to two weeks. During the ongoing Omicron surge, prior authorization waivers for PAC services have been rare and those that have been offered have typically been for small amounts of time, and often excluded certain provider types or services.

These inconsistencies in the application of waivers, as well as restrictions on provider types, have been particularly problematic for PAC providers, as some plans excluded PAC hospitals (specifically LTCHs and IRFs) entirely from the waivers, or only allowed waivers specifically for LTCH ventilator patients. Other plans only applied waivers to SNFs. These exclusions directly inhibited pandemic response activities, denying PAC facilities from much-needed relief from administrative burdens during a time of emergency.

It is also important to note that there are disparities between the application of prior authorization and the use of waivers during the PHE between MA and other markets, often with less flexibility being offered by MA plans. For example, in some states, certain insurance plans operate both a MA plan and Medicaid managed care plan. While many of these plans offered full prior authorization waivers under their Medicaid managed care line of business during the PHE, as required by many states, the same plans often did not extend waivers to their MA lines of business, or did so sparingly. Notably, many of the state-mandated waivers of prior authorization in Medicaid managed care are still in effect, while MA plans have largely returned to business as usual even while the emergency persists.

Lengthy and Inconsistent Prior Authorization Determinations and Appeals

Our members estimate that it takes MA plans who did not waive prior authorization requirements during the PHE approximately three days to respond to an authorization request for PAC. The total turnaround time can be much greater for denials that include plan requests for additional information or require subsequent appeals. In addition, if the plan requires a peer-to-peer consult during the denial reconsideration process, this can add an additional two to three days to the turnaround time, depending on the plan. Notably, the day that the request is received by the plan does not count in determining turnaround time, even though the patient remains on standby that day. Further, since prior authorization reviews often are on hold during weekends, patients with in-process reviews remain on standby on Saturdays and Sundays, waiting for the health plan’s response to authorize the next steps of their care.

Furthermore, it appears that some MA plans currently have higher prior authorization denial rates than prior to the PHE, pointing to a concerning trend, especially during an ongoing PHE. Specifically, one multi-state member reports that for the two plans covering the largest portion of their MA cases, prior authorization denial rates for their LTCHs dropped slightly during 2020, but were substantially higher in 2021 and 2022 to date, relative to the pre-PHE years. Specifically, LTCH denial rates for this member’s largest MA plan increased nearly 13% from 30.7% in 2018 to 43.4% to date in 2022, reflecting that nearly half of all LTCH requests for prior approval are denied by this plan. This reflects a pattern of aggressive authorization denials that is common among MA plans, especially for PAC services, which unfairly delays and limits access to care for thousands of patients. It also illustrates that during a time when CMS has encouraged MA plans to offer waivers of prior authorization requirements, some plans have not only refused to relax these requirements but have actually increased denials over the duration of the ongoing PHE. These patterns are very concerning for general acute-care hospitals and their PAC partners, and we believe warrant further examination by CMS to consider the effects of these fluctuations in prior authorization denials by plan during periods of national emergency.

In addition, from a PAC perspective, there are widely-held concerns about the behavior of MA plans who approve prior authorization requests for PAC, but later issue retrospective denials for the same services. This has been a long-standing and problematic issue for many PAC providers and the resulting hesitancy also contributed to delays in patient transfers from general acute-care hospitals to PAC facilities during the PHE. However, despite these concerns, some LTCH members opted to admit patients being discharged from a general acute-care hospital without waiting for prior authorization approval during COVID-19 surges, acting in good faith to support the PHE response and prioritize patient well-being. Unfortunately, some of these cases were ultimately denied by the MA plan.

Finally, our PAC members flagged several additional concerns about the appeals process for prior authorization denials, which further complicate and delay this already fraught process. In these members’ experiences:

- Appeals to the third-party MA appeals administrator are submitted and administered by the health plan, in an apparent conflict of interest given the plans’ lack of neutrality.

- The MA third-party appeals administrator provides its appeals determination via phone to the provider, while the beneficiary receives a written response. This limits transparency of the clinical and/or technical basis for the denial and precludes the provider from having a written record to evaluate and respond to in advocating for patients.

To better understand current MA plan practices and to identify opportunities for process improvement, we urge CMS to evaluate plan-to-plan differences in both process and turnaround times for prior authorization review, and to require that these processes be more standardized and transparent for providers and members.

Unwarranted Prior Authorization Delays Harm Patient Care

It is clear that delaying a patient discharge that has been prescribed by the treating physician in order to wait for the health plan’s response to a prior authorization request is not in the best interest of the patient. These delays often result in missed clinical opportunities for patients to access the more-specialized care provided in PAC settings. It is a detriment to patients with or recovering from COVID-19 whose condition requires interdisciplinary and targeted PAC care that combines medical care and rehabilitation. This is particularly important for high-complexity patients and those experiencing cases of “long-COVID-19.” This type of interference with the plan of care prescribed by the treating physician in the referring hospital can reduce clinical progress as the patient awaits a transfer, ultimately delaying the return to home or community settings.

These concerns are consistent with the findings of a September 2018 report by the Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (OIG), which warned that high rates of MA health plan payment denials and prior authorization delays could negatively impact patient access to care.1 Further, a 2021 survey by the American Medical Association of more than 1,000 physicians underscores the negative impact on patient care resulting from prior authorization. The survey found that more than one-third (34%) of physicians reported that prior authorization led to a serious adverse event, such as hospitalization, disability or even death, for a patient in their care. Also, more than nine in 10 physicians (93%) reported care delays while waiting for health insurers to authorize necessary care, and more than four in five physicians (82%) said patients abandon treatment due to authorization struggles with health insurers.2

MA Prior Authorization and More Restrictive Admissions Criteria May Inappropriately Limit PAC Coverage

There are substantial documented differences in the use of certain PAC among patients enrolled in MA versus Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS), which we believe may be the result of overly restrictive authorization practices applied in MA that have the potential to limit access to appropriate PAC services. Specifically, an analysis conducted by the National Association of Long Term Hospitals found that in 2015, MA beneficiaries were approximately half as likely as Medicare FFS beneficiaries to receive services at an LTCH (44%) or an IRF (53%), and 9% less likely to use SNFs relative to their FFS counterparts.3

In addition, there appear to be differences in patient characteristics and measures of severity between patients utilizing PAC services in MA versus Medicare FFS, which further suggests that restrictive MA authorization criteria may play a role in limiting access to necessary PAC services. To further examine this dynamic, AHA compared two clinical indicators for patients enrolled in MA and Medicare FFS who were discharged from general acute-care hospitals paid under the inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS) to a PAC setting: mean case-mix index (CMI)4 and mean length of stay (LOS) in the referring hospital.5

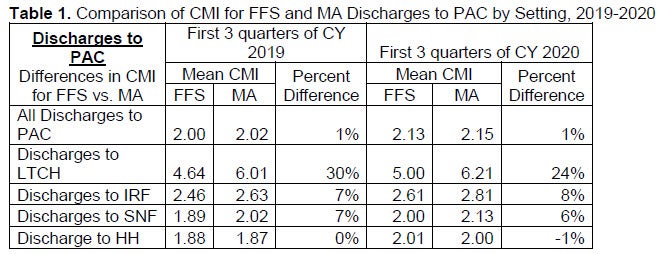

Mean CMI. As shown in Table 1, the mean CMI for MA discharges to LTCHs is substantially higher than the mean weight for Medicare FFS discharges (30% greater in 2019 and 24% in 2020), and somewhat higher for IRFs and SNFs (8% and 6%, respectively, in 2020, and 7% for both in 2019).

It is possible that excessive MA prior authorization processes may contribute to the higher CMI levels among MA enrollees receiving care in the IRF, SNF and LTCH settings, resulting in access only for the most sick and complex patients, while limiting access to others who would benefit from clinically appropriate PAC services. At a minimum, this variation warrants closer study to determine whether there is a correlation between higher CMI levels among MA enrollees and restrictive PAC admissions criteria — and whether this results in unequal access to PAC services between the two subgroups of Medicare beneficiaries.

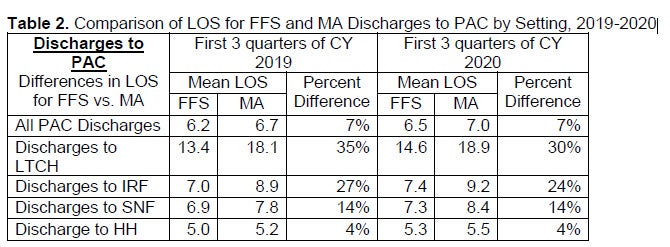

Mean LOS. The data summarized in Table 2 indicates that MA patients discharged to PAC settings have a longer LOS in the referring hospital compared to Medicare FFS patients who are discharged to PAC settings, both prior to and during the PHE. The difference in LOS between MA and FFS patients is particularly large for patients discharged to LTCHs, with IRFs and SNFs also showing sizable disparities.

These differences in LOS warrant close examination by policymakers to identify why MA patients are staying much longer in the referring hospital, even during the PHE, and to better understand the ramifications of these patterns. This examination should consider the multiple drivers affecting discharge and how these processes vary between MA and FFS Medicare, including prior authorization processes, PAC admissions criteria, relative case-mix levels, top diagnostic categories, clinical competencies of downstream PAC providers, and other variables.

At a minimum, these data on CMI and LOS raise initial questions about whether more restrictive MA admissions criteria inappropriately limit access to needed PAC services to only the most severe patient cases. It also points to the need for greater understanding of the criteria guiding the discharge of MA patients to PAC and the processes for approving such care. Some specific actions that would help to improve transparency in this area include:

- Publicly evaluate the discharge and PAC admissions criteria being used by MA plans to ensure transparency and consistency across plans.

- Compare MA and Medicare FFS coverage and admissions criteria for PAC services to determine if MA plans are ensuring equal access to PAC services as required.

- Identify types of PAC services that are covered under Medicare FFS, but commonly declined by MA plans, which may suggest an inappropriate narrowing of PAC coverage by MA plans.

Health Plans Adding Administrative Burden to the National PHE Response

Many MA plans use inconsistent administrative protocols and a dizzying array of timelines and requirements for prior authorization requests, reviews, approvals and communication, which are unnecessary at best, but rise to the level of unconscionable during a PHE. Excessive requirements and variation between them adds burden to the system as providers and their staff must ensure they are following the right set of rules and processes for each plan, which may change from one request to the next, and can also vary by plan, product and vendor. Despite the tremendous time and resources needed to comply with such extensive requirements, prior authorization requests are often returned multiple times for additional information and are further delayed by slow health plan responses, which typically do not occur outside traditional business hours. During a time of national emergency where workforce shortages and strained health system capacity have been persistent challenges, there is simply insufficient bandwidth to comply with such cumbersome administrative procedures.

In addition, we believe prior authorization is frequently overused in cases where there is no established basis for its use. For example, some health plans require prior authorization even for services where there is no evidence of abuse and for which the standards of care are well established.

Specifically for PAC services, health plans frequently deny the presence of medical necessity for services that are supported by the literature and that are covered by Medicare FFS. For example, despite clear clinical guidelines directing providers to place certain medically-complex stroke patients in IRFs for a combination of medical and intensive rehabilitation services, health plans commonly require prior authorization or even deny this service.

Excessive Prior Authorization Exacerbates Workforce Challenges

Prior authorization processes have exacerbated workforce challenges and contributed to physician and other staff burnout during the PHE. Hospitals often have multiple full-time employees whose sole role is to manage health plan prior authorization requests. These staff often are physicians and nurses who have been diverted from patient care. Part of the challenge stems from health plans’ use of peer-to-peer calls to establish prior authorization for a service or treatment without providing access to clinicians with the right type of expertise. Physicians report that their offices spend on average two business days of the week dealing with prior authorization requests, with 88% rating the burden level as high or extremely high.6

Lack of Transparency of Clinical Guidelines

Health plans commonly use medical necessity criteria and other clinical guidelines for general acute-care hospital and PAC admissions, which differ by plan and deviate from those used by Medicare FFS. These modifications often are deemed proprietary and not shared with providers, resulting in a black box methodology for determining whether a service is medically necessary. As a result, it becomes nearly impossible for providers to anticipate what the health plan might request as evidence of medical necessity pursuant to a criteria that they will not share.

As a result of this lack of transparency in clinical guidelines, there is often extensive back and forth between providers and health plans in response to insurer requests for excessive amounts of documentation to substantiate the need for particular services. It is not uncommon for health plans to request information that is not directly relevant to making a determination about whether post-acute care is needed (e.g., when evaluating a prior authorization request for rehabilitation services, requesting information on a medication that would not impact the need for rehabilitation services, etc.). Further, with regard to transitions to PAC, the medical judgement of the treating physician who actually examined the patient is often overridden by the plan’s clinical staff, which is often a registered nurse or other clinician with little or no PAC clinical expertise.

OIG Found Unwarranted MA Denials

The majority of the prior authorization and coverage denials are for covered, medically necessary services that are rejected for administrative processing reasons as opposed to concerns about the legitimacy or appropriateness of the service. Generally in these cases, clinicians treat patients using their best medical judgment, but too often their expert opinion is overridden by the plan (and often by a clinician without relevant expertise in the particular specialty or PAC discipline). Ultimately, many of these denials are overturned through time-consuming administrative appeals. The September 2018 OIG report referenced earlier found that among appealed cases from 2014-2016, MA plans overturned 75% of their own denials (approximately 216,000 denials per year) through their own appeals processes.7 These findings highlight a pattern of health plans inappropriately denying access to services and payment that should have been provided.

Urgent and continued action is needed to ensure that health plans’ administrative processes do not impede patients’ ability to receive timely, quality, medically necessary care in clinically appropriate downstream settings. This is more important than ever as we continue into our third year of a global pandemic, fighting new variants and surges, administering additional vaccine doses, addressing workforce shortages, and maintaining critical testing and treatment capacity. We again urge CMS, working with Congress, to establish the authority to require — not just encourage — health plans to waive these processes during PHEs.

REQUEST FOR INFORMATION ON BUILDING BEHAVIORAL HEALTH SPECIALTIES WITHIN MA NETWORKS

In this rule, CMS seeks to increase its understanding of issues related to accessing behavioral health specialties for MA plan enrollees, specifically regarding the challenges Medicare Advantage Organizations (MAOs) face in building an adequate network of behavioral health providers. The AHA appreciates CMS’s focus on improving access to behavioral health services under MA, and encourages the agency to approach the problem within the context of the administrative barriers erected by insurers, which often result in delayed or restricted access to critical services.

While access issues for behavioral health services are unfortunately a common problem across payers, the experiences of our member hospital and health systems highlight that administrative barriers are uniquely pervasive in the MA market, and often result in direct harm to patients. Examples of such barriers include delays in prior authorization decisions; payment denials for care that has been pre-authorized; multiple requests for records; inadequate behavioral health specialties within provider networks; unilateral, mid-year changes in reimbursement policies; and site of service exclusions. As a result of these practices, individuals experiencing behavioral health crises are often unable to access the care and services they need, and often spend extended periods waiting for placement in inappropriate settings (like the emergency department) as medical staff wade through onerous administrative processes to satisfy a dizzying array of payer requirements.

Regulators have largely deferred to the dispute resolution mechanisms in provider/health plan contracts to address these problems, as federal law places restrictions on the government’s ability to intervene in “contractual disputes.” However, we believe strongly that health plans should be held accountable for ensuring access to behavioral health services, as required by law. Failure to do so comes at the expense of patients and families who are in need of support, and is especially troubling during a time of national emergency when the demand for behavioral health is at an all-time high.

Provider Shortages

The nation is grappling with critical workforce shortages in specialized behavioral health disciplines, particularly for providers who can prescribe medication-assisted therapy, psychiatric nurses, and residential treatment providers. According to a survey of AHA members from the fall of 2019, hospitals and health systems found inpatient mental health and substance use disorder recovery services most difficult for their patients to access, followed by placement in inpatient psychiatric facilities. In addition, members report challenges finding providers that offer medication-assisted therapy and residential care for substance use disorder and hospital-based outpatient behavioral health services like partial hospitalization programs. Finally, and perhaps most relevant for MA plans, there is a shortage of medical-based mental health resources specialized for distinct populations—namely, geriatric psychiatry.

These shortages and access challenges are exacerbated by stringent and outdated requirements for licensing, board certification, credentialing and scope-of-practice, which restrict who can participate in networks (for example, peer counselors and other substance use disorder specialists). Addressing these issues is a necessary step to strengthen the behavioral health workforce in tandem with other strategies. MA plans should also work to expand their geographic reach (e.g., through use of telehealth services or creative contract agreements with community organizations), harness the power of data to better understand the behavioral health needs of their enrollees and address considerations for what constitutes an “adequate” network.

Defining an Adequate Network

Part of the problem with the general requirements to build an adequate network is the lack of specificity in the definition of “adequate.” To be considered sufficient, an insurer might only need to have a single licensed, accredited or certified professional listed in its provider directory who purports to provide behavioral health care. However, providing behavioral health care can refer to a wide range of subspecialists with varying areas of expertise in mental health and substance use disorder treatment. MA plan behavioral health providers may not have the appropriate clinical expertise to meet the specific needs of all plan enrollees. For example, a network that includes a hospital with an outpatient eating disorder clinic would not be adequate for an enrollee seeking medication-assisted therapy for opioid use disorder, even though the clinic provides a certain type of behavioral health service. Similarly, contracting with certified professionals does not ensure that those providers are certified in subspecialties needed in the enrollee population or community. A psychiatrist without expertise in geriatric mental health may meet technical standards, but would still leave a gap in services for certain populations.

Administrative Barriers

While provider shortages can certainly threaten access to behavioral health care for MA enrollees, patients face other insurer-created hurdles that delay or restrict access to care even when providers are available to meet their needs. Administrative barriers, as described above, are commonly put in place by MA plans as a way to control utilization and cost, often at the expense of patients and timely access to care. Our members are plagued by plans that automatically deny coverage for behavioral health services as a regular procedure, especially in MA products. In some markets, members report that MA denial rates are significantly higher than the overall Medicare denial rate.

While plans cite many reasons for denying behavioral health claims based on ineligibility, our members report a broad range of reasons for regular denial of these services which are administrative in nature. For example, eligibility criteria for admission to an inpatient psychiatric facility can differ by the type of software used by various plans, resulting in unnecessary denials. Or adding comorbidities to a patient’s chart after admission might result in a denial at discharge. These issues are further compounded by health plans changing eligibility criteria without notice, and requiring copious amounts of information that often is not medically relevant for the service being requested.

As described in the previous section, there is substantive evidence that most denials are unnecessary and later overturned, and that MA plans are denying services that should be rightfully covered as a matter of routine practice. These administrative barriers, which are ultimately designed to inflate health plan profits, take significant time and effort for medical and administrative staff, and directly limit patient access to behavioral health care.

Narrow Networks

Another administrative barrier that may limit access — and may affect a beneficiary’s decision to enroll in MA to begin with — is the insurance construct of narrow networks. While insurers have developed narrow networks in an effort to negotiate lower rates while maintaining a network of high quality providers, the growth in narrow networks in recent years has generated new concerns about limiting patient access. According to a 2019 Health Affairs study, “some policy makers have raised concerns that networks may have become excessively restrictive over time, potentially interfering with patients’ access to providers.”8 This has been particularly problematic in behavioral health specialties.

While the exact breadth of MA networks varies by locality, MA plans use narrow networks more often for psychiatric care than any other specialty. The Kaiser Family Foundation found that, on average, MA plans included less than one-quarter of psychiatrists in a county, and more than a third included less than 10% of psychiatrists in their county.9 This means that a beneficiary of traditional Medicare receiving care for serious mental health issues would likely need to find a new provider if they were to enroll in an MA plan. In general, MA plan networks are unlikely to include specialized behavioral health providers who can deliver services necessary for beneficiaries with complex behavioral health needs. This dynamic is reflected in a 2019 study by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which found that patients went out of network in their MA plan more frequently for mental health services than for comparison services.10

Effects of Higher Patient Cost-Sharing

In addition to a lack of options for care, patients tend to pay more for mental health services than for other medical services under MA. This difference is driven by higher in-network cost sharing for mental health services. As found in the same CBO study, MA patients paid an average of $9 more for mental health services than for comparison services in-network. These disparities in insurance benefit design further restrict access to care and may discourage patients from seeking help when needed. Patients may also be discouraged from enrolling in MA plans to begin with, or may be surprised with higher-than-expected out-of-pocket costs at the point of service.

Disparities in Payment Rates between MA and Medicare FFS

Part of the reason behavioral health networks are often lacking is due to the challenges in establishing contracts between specialized behavioral health providers and MA plans. Contracting is limited by the prices MA plans pay for in-network mental health services, which are significantly lower than what Medicare FFS pays for identical services. According to the aforementioned CBO study, MA plans paid an average of 13%-14% less for in-network mental health services than Medicare FFS, despite paying up to 12% more than Medicare when the same services were provided by other specialties. This reflects a substantive inequity in payment for mental and behavioral health services enrolled in MA products, which further exacerbates provider shortages in these critical disciplines, and limits the availability of in-network behavioral health providers.

Contracting and Unequal Market Power

Another challenge for behavioral health providers to establish contracts with MA plans is the imbalance in market power. In some regions, contracting is done through a multi-state consortium rather than between MA plans and individual health systems or even in the statewide market. In this largescale marketplace environment, certain behavioral health providers, such as freestanding inpatient psychiatric hospitals, may lack the market power to establish favorable contracts, resulting in more limited networks and restricted access to behavioral health services in some regions.

While the experiences our members have had with MA plans differs by issuer and region, we believe addressing these pervasive barriers to behavioral health care requires thoughtful oversight, as well as improved data collection and reporting. We recommend that CMS collect and publicly display data that indicate the adequacy of MA coverage for behavioral health care. Data might include information on appeal overturn rates and issuer/regional variation; denials by level of care; and availability of specific behavioral health services including geriatric mental health, substance use disorder treatment (including medication-assisted therapy), and crisis stabilization services.

We thank you for the opportunity to comment on these important topics and for your attention to the concerns we have raised. Please contact me if you have any questions, or feel free to have a member of your team contact Michelle Kielty Millerick, senior associate director for health insurance and coverage policy at mmillerick@aha.org.

Sincerely,

/s/

Stacey Hughes

Executive Vice President

_________

1 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General (OIG). “Medicare Advantage Appeal Outcomes and Audit Findings Raise Concerns about Service and Payment Denials.” September 25, 2018. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-09-16-00410.asp.

2 American Medical Association, “2021 AMA Prior Authorization (PA) Physician Survey.” https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/prior-authorization-survey.pdf.

3 National Association of Long Term Hospitals (NALTH), “Medicare Advantage Limits Use of Long-Term Care Hospitals; Users Have Significantly Higher Severity than in Traditional Medicare,” Feb. 10, 2021.

4 CMI is a measure of patient severity; higher CMI indicates that patients require more resource-intensive services.

5 The analysis used the fiscal year 2019 and 2020 Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) files and specifically looked at discharges in the first three quarters of calendar years (CY) 2019 (prePHE) and 2020 (PHE). Since the last quarter of CY 2020 is not in the MedPAR file, we used comparable quarters/time periods.

6 https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/prior-authorization-survey.pdf.

7 https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-09-16-00410.asp

8 Feyman Y., Figueroa J., Polsky D., Adelberg M., and Austin Frakt, “Primary Care Physician Networks in Medicare Advantage.” Health Affairs, Vol. 38, No. 4, April 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05501

9 “Medicare Advantage: How Robust Are Plans’ Physician Networks?” Kaiser Family Foundation, October 2017. https://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Medicare-Advantage-How-Robust-Are-Plans-PhysicianNetworks

10 Pelech D. and Tamara Hayford, “Datawatch: Medicare Advantage and Commercial Prices for Mental Health Services,” Health Affairs, Vol. 38, No. 2, February 2019. https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/pdf/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05226