3 Keys to Addressing the Rural Maternal Health Crisis

For the better part of the last decade, St. Anthony Regional Hospital has prioritized ways to improve birth outcomes in the six-county rural area it serves in west central Iowa.

Its providers have extended their practices to satellite locations, bringing prenatal care to three communities that previously lacked these services. St. Anthony invested in its Birth Place program nursing staff, resulting in five specialty certifications in lactation and electronic fetal monitoring. It also has recruited three new family practitioners who offer obstetrical (OB) health services.

And since 2017, St. Anthony has seen improvements in patients who enrolled in prenatal care during the first trimester, birth weights and birth rates among teens.

Critical Lifeline Threatened

Efforts like these are taking on greater importance as the number of U.S. rural hospitals in general and those with obstetric services continue to decline and efforts to recruit obstetricians and other physicians remain challenging. Since 2000, 42 Iowa hospitals have closed OB services due to a declining population and an inability to recruit and retain physicians willing or able to provide OB care. Iowa’s situation is reflective of national trends. Between 2015 and 2019, at least 89 obstetric units closed in rural hospitals, notes an AHA infographic released last year.

Just last month, two rural facilities — OhioHealth Shelby Hospital and University Hospitals Lake West Medical Center — ended their maternity services. And in Sandpoint, Idaho, Bonner General Health stated recently it will end obstetric services in May. These closings are related to the declining number of deliveries at the facilities, but Bonner also cites the lack of qualified doctors and nurses in the state as reasons for its decision.

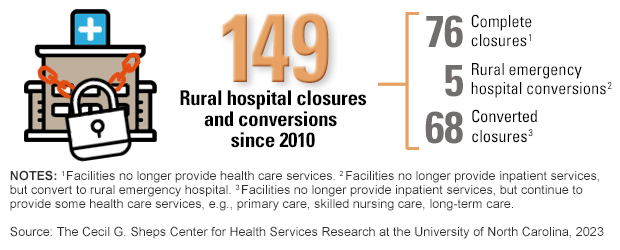

Rural hospitals, which deliver about one in 10 babies nationally each year, also have been closing in significant numbers. Since 2010, there have been 149 rural hospital closures and conversions that involved ending inpatient services, according to data from The Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina. In rural counties, the loss of hospital-based obstetric care is associated with an increase in preterm births, distance traveled for obstetric care, out-of-hospital births and births in hospitals with obstetric units, according to a U.S. Government Accountability Office report from last fall.

Despite the challenging environment, rural hospitals and health systems are taking traditional and innovative approaches to build or expand their maternal health programs.

3 Ways to Build Rural Maternal Health Resources

1 | Expand access to prenatal care and clinicians.

1 | Expand access to prenatal care and clinicians.

Kearny County Hospital, Lakin, Kansas, launched its Pioneer Baby program in 2015 with Kansas University School of Medicine–Wichita to improve pregnancy and birth outcomes by reducing complications, premature births, low or extremely high birthweight and cesarean sections while increasing breastfeeding rates.

The program offers participants the Becoming a Mom prenatal curriculum, a virtual breastfeeding network, a breastfeeding walk-in clinic and a diabetes-prevention program. Kearny’s outreach clinic is staffed by a perinatologist one day a month who sees high-risk obstetric patients and offers recommendations on perinatal care. Kearny also has focused on quantitative blood-loss initiatives, OB hemorrhage risk assessment, timely treatment for hypertension and preeclampsia and participates in a neonatal abstinence syndrome program.

Increased resources for the program were paid for in part by funding from the Children’s Miracle Network. Meanwhile, the hospital has increased its number of delivering providers from four to seven, increased nurse training and expanded its prenatal curriculum. These and other efforts helped the hospital steadily increase the number of births per year from 286 in 2020 to 339 births last year while reducing the primary C-section rate from 13.6% to 13.0% during that period.

2 | Explore partnerships to meet critical care needs.

2 | Explore partnerships to meet critical care needs.

Intermountain Primary Children’s Hospital recently launched a new telehealth program to extend care from providers within its neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) neurology program to more locations, enhancing care for critically ill and injured newborns.

By expanding this service through telehealth, the children’s hospital neurologists will be able to monitor babies remotely while recommending treatments for caregivers within four Level III NICUs, three of which are in Utah and one in Billings, Montana. This will enable clinicians to keep babies close to home rather than immediately transferring them, potentially reducing costs.

3 | Make telehealth services easier to access.

3 | Make telehealth services easier to access.

A 2021 study found that women who live in remote areas of the U.S. could benefit from telehealth, which would reduce the number of in-person visits needed for prenatal care and increase access to care. The study suggests that expanding prenatal telehealth appointments could help women in remote areas better adhere to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' recommendation of 12-14 prenatal care appointments for those with low-risk pregnancies.